Creating Space for Reflection: Meaning-Making Feedback in Instrumental/Vocal Lessons

- Ingesund School of Music, Department for Artistic Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Science, Karlstad University, Arvika, Sweden

In higher music education, problems have been reported regarding students’ lack of independence in one-to-one instrumental/vocal lessons, little space for reflection, and education based on a hierarchical master–apprentice tradition, regulating and restricting students’ opportunities to learn and reflect. This article concerns video-recorded feedback activities in one-to-one instrumental/vocal lessons in specialist music teacher education, paying special attention to the space offered for student self-reflection and independence. The data comprise video-recorded one-to-one instrumental/vocal lessons between students and teachers. A social semiotic perspective is used to study representations of feedback meaning-making in the interaction between students and teachers as well as the understandings and approaches related to traditions and norms in music education. The findings indicate that feedback is constructed through two contrasting discourses, resulting in various ways of realizing feedback related to reflection opportunities. The negotiating discourse emphasizes opportunities for student self-reflections, drawing on current institutional curricula and government requirements regarding reflection abilities. In contrast, the controlling discourse emphasizes constraints on such opportunities, connected to the hierarchical master–apprentice music tradition. The feedback approaches realizing these discourses are described in terms of space for conversation or exploration as well as a call for attention or re-creation, evident in all studied lessons. The discussion addresses some didactic issues regarding the findings.

Introduction

This study examines feedback situations in one-to-one instrumental/vocal teaching in Swedish specialist music teacher programs, paying specific attention to how self-reflection and independence are given space in teacher–student interaction. The ability to critically and independently “reflect on [one’s] own and others’ experiences” (Swedish Code of Statutes [SFS], 2010) is a required learning outcome in all vocational programs in Sweden. Also, reflection abilities are expected as a learning outcome in all education systems in Sweden (Swedish Code of Statutes [SFS], 2009) and many other European countries (Gaunt, 2016). With this learning outcome implemented in music teacher education programs, students’ reflections can be expected to be used in individual instrumental/vocal teaching.

In the literature, feedback is described as one type of activity in the domain of formative assessment practice, defined by Black and Wiliam (2009) as an activity to elicit, interpret and use evidence of student achievement in order to make decisions about the next instructional step. In such decision-makings, the agents, including both teachers and learners and their peers, and the possibility to create discussions are considered important. Feedback is also understood as a strategy to move learners forward (Black and Wiliam, 2009) and as an information provided by a teacher or a peer, regarding aspects of the learners understanding or performance (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). Hattie and Timperley propose that feedback questions regarding goals, progress and feed forward activities have to work together to be reflected and answered, unless they can inhibit the effect of feedback on learning.

The concept reflection is described by several authors in ways appropriate for this study. Dewey (1910/2003) defines reflection as a meaning-making process of experiences related to other experiences, transformed into knowledge that can be practiced. In a similar way, Schön (1984) points out that reflection-in-action is the core of practice with due to its intertwining of thinking and doing. Also, when a practitioner reflects-in-action, it is a form of intuitive understanding, embodied as a feel for the artistic performance. However, Schön also points out that reflecting-on-action, with descriptions of intuitive knowing, can feed reflections and enable individuals to restructure, test and criticize their understandings. Related to artists, Crispin (2021) argues that, even though the reflection is framed verbally, the reflection itself resides inside the artistic practice as a knowing in performing. Since the study concerns musical practices, the concepts of reflection in and on action fits these practices well.

The described definitions of feedback and reflection raises questions of how reflection can be realized in feedback situations in music education, especially when previous research has reported problems regarding students’ opportunities to reflect during teaching (Gaunt, 2008) due to restricted learning practices in Nerland (2007) and reproduction of the master–apprentice teaching tradition (Bull, 2019). The aim of this study is to explore how opportunities for student reflection in feedback situations are constructed and realized in one-to-one instrumental/vocal lessons in specialist music teacher education.

Feedback and Reflection in Teaching

Feedback through teachers’ use of embodied and musical demonstration as well as verbal comments and reflections, in response to students’ own playing or singing, is common in higher music education (Gaunt, 2008; Sandberg-Jurström, 2016; Georgii-Hemming et al., 2020), music education in public school systems (Cranmore and Wilhelm, 2017), and music instruction outside the school system (Sandberg-Jurström, 2009). However, one-to-one instrumental/vocal teaching in higher music education has been described as a “relatively passive process of direct copying” (Burwell, 2013, p. 280) and as the reproduction of knowledge through students’ trusting their teachers’ knowledge and experience as musical experts (Gaunt, 2011; Holgersson, 2011; Laes and Westerlund, 2018). This relationship is explained as a teacher–student power dynamic, with the teacher controlling rather than negotiating the interaction (Gaunt, 2011). These education models, derived from a master-apprentice tradition common in instrumental/vocal tuitions (Burwell et al., 2019), is also considered to be governed by discursive practices (Nerland, 2007) and regulated by a certain musical belief system (Christophersen, 2012) as to what is legitimate to know and learn. Additionally, such education reportedly inhibits students’ development of self-responsibility, own individual artistic voice, and ownership of the learning process (Gaunt, 2008). Although individual instrumental/vocal lessons are considered to offer students powerful learning models, such as instruction, advising, and coaching (Gaunt et al., 2012) as well as explanation, guidance, imitation, and feedback (Burwell, 2012), they also offer a tradition of teaching these models in isolation (Gaunt, 2008, 2011; Burwell, 2012), hidden behind closed doors (Carey et al., 2013). Also, social approaches to learning and teaching, such as nurturing and cultivating aspects, have been used in one-to-one tuition (Hallam, 1998). Nevertheless, lessons are often described as “secret gardens” (Burwell et al., 2019) where teachers’ work might appear to be private interaction characterized by “businesslike intimacy” with non-verbal interaction (Burwell, 2012, p. 150), and with few opportunities for teachers to engage in shared exchange and reflection (Gaunt, 2016). The lack of reflection opportunities in such situations can be seen as problematic due to universities’ requirements to promote increased equality and strengthened democracy in society as well as lifelong learning, while striving to renew content and teaching methods to achieve lasting participation in the knowledge society (SOU, 2001). That classical music practices in higher music education reportedly legitimize competition, hierarchy, and exclusion, and that this tradition is recreated year after year by educational institutions (Bull, 2019) and is difficult to change (Georgii-Hemming and Westervall, 2010; Jordhus-Lier, 2018), contribute to the problem. In addition, Burwell et al. (2019) has stated that completely cloistered reproduction cycles, in which apprentices themselves become masters teaching skills in isolation, have no place in the twenty-first century.

Even though critical reflection is not considered particularly evident in higher music education institutions, competence in critical thinking and reflection are still emphasized in order for students to become lifelong learners (Johansson and Georgii-Hemming, 2021). Reflective practices in higher music education are considered to have potential to enhance students’ ability to take responsibility for their own learning (Carey et al., 2016), create opportunities for deeper understanding of learning practices (Esslin-Peard et al., 2016), contribute to artistic knowledge development, and secure professional musical success (Georgii-Hemming et al., 2020). Also, as pointed out by Hallam and Bautista (2012), some of the most important regarding musical learning is to provide appropriate opportunities for feedback, reflection, understanding, and meta-cognition. In line with this, Creech and Gaunt (2012) emphasize that a shift from the traditional master-apprentice model is required to implement a more facilitative model where students and teachers reflect, collaborate, and problem-solve together. Likewise, the importance of working in shared knowledge communities of an expert culture, with focus on collaborative activities, innovation and creativity is highlighted (Hakkarainen, 2016). Such a shift from an instructional pedagogical approach to learning through students’ own experiences is considered to benefit the students (Lebler, 2016). As an example, students’ self-reflection using multimodal resources in music, dance, and fashion in higher art education has resulted in improved reflective practices (Barton and Ryan, 2014). Also, students’ extensive reflective work upon their own actions in video documented vocal lessons has resulted in opportunities to utilize the knowledge offered by their teachers (Johansson, 2013). In such cases, music teachers’ reflections on their own teaching processes are considered important for encouraging collaborative dialogues among students, enabling them to build their own approach to learning (Latukefu and Verenikina, 2016). For example, feedback comments in collaborative music classrooms can serve as an opportunity to share personal anecdotes or details, establishing a sense of comfort and intimacy (Chapman Hill, 2019) as well as that collaborative learning with and from peers can create an environment appropriate for mentoring, where students can develop reflective interaction (Gaunt et al., 2012). Also, it is considered that students’ critical reflections related to other students’ contributions in collaborative practices provide a deeper learning as well as a deeper interaction and engagement among the peers (Johansen and Nielsen, 2019). Given the requirement for upper secondary school students to “reflect on their experiences and their individual ways of learning” (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2013, p. 8), developing future music teachers’ critical thinking and reflection on learning processes is crucial.

Approaches to Exploring Feedback Situations

To capture how feedback is used in teacher–student interaction in one-to-one instrumental/vocal teaching in specialist music teacher education, a theoretical design was chosen focusing on how individuals use meaning-making modes, such as bodily gestures, music instrument playing, singing, gaze, and speech, to make sense of the world. In this study, the interest is in rendering such meaning-making activities visible, and in how participants, in accordance with Kress (2010), represent and communicate approaches and attitudes to various phenomena, in this case, how feedback situations emphasizing opportunities for reflection are constructed and realized. In such processes, the term transformation signals the re-articulation of meaning from one to the same mode, for example, from a teacher’s use of a saxophone to a student’s response using the same instrument, whereas transduction signals the re-articulation of meaning from one mode to another, for example, from a teacher’s use of speech to a student’s use of singing. In this study, this implies a focus on teachers’ and students’ knowledge representations through their use of modes, related to attitudes and understandings produced in meaning-making feedback situations during lessons. From this perspective, meaning-making is seen as dependent on the discourses produced in a certain context. With reference to Kress (2010), discourse signals what institutions, such as education or the family, consider knowledge about the world and thus how meanings about the world are organized, produced, and shaped by the “perspectives of a particular institution” (Kress, 2010, p. 110), while multimodal meaning-making is seen as the articulation and realization of discourses. This implies that modes, with their affordances of culturally and socially constructed semiotic resources, let individuals make meanings by representing what they regard as knowledge of the world and the things they want to represent in a certain context, in this case, how ideas regarding reflection opportunities in feedback situations are represented in instrumental/vocal lessons.

Here, feedback is not seen as a question of evaluating the learners, but, in line with Kress (2009), more as an intention to recognize signs of learning, i.e., to hear or see the result of a semiotic meaning-making engagement. In this sense, the study takes into account the view that engagement in the student’s learning process is a question of facilitating learning by using, as Black and Wiliam (2009) advocate, strategies that provide useful lenses for teachers. Providing feedback that moves learners forward is an interesting aspect of the focus on students’ opportunities for reflection in instrumental/vocal teaching. The question of how to create activities that engender progress and feed-forward is in line with this perspective, as is self-feedback oriented to the learners themselves (Hattie and Timperley, 2007).

Materials and Methods

Methods

To illustrate the complexity of participants’ use of meaning-making resources (Jewitt, 2006), their interaction and relationships (Baldry and Thibault, 2006), and the understandings and approaches produced in the social practice (Kress, 2010), video documentation, with detailed transcripts (Jewitt, 2006) was used for data collection. The data comprise 18 video-documented instrumental lessons with six teachers and their respective students, a total of three lessons per teacher–student pair, representing several instruments and genres.

Participants and Procedure

Several instrumental teachers at one specialist music teacher educational institution in Sweden were asked to participate in the study. The teachers were chosen based on a desire to sample lessons based on various musical genres and instruments. The six teachers who agreed to participate received written information about the aim and the implementation of the project as well as guidelines regarding de-identification and voluntary participation before signing a written consent form. After that, the teachers asked students to participate, and the six students who agreed received the same information before signing the consent form. These students were all music teacher students from varying grades. Before the study started, both teachers and students were informed about the study’s focus on feedback. They were therefore urged to pay attention to feedback aspects in their lessons, a fact that may have influenced their choice of content and implementation. The video recordings were produced by the teachers over an 8-week period. The lessons lasted 30 min to one hour, and all of them involved the students playing or singing one to three pieces of music on which the teachers made comments.

Analyses

The video recordings were first transcribed with a focus on identifying feedback sequences, after which a detailed transcription was made of the use of modes in feedback sequences in the last six video-recorded lessons. These sequences were analyzed in relation to Halliday’s (2013) three meaning-making principles and functions, the ideational, the interpersonal and the textual functions, of language communication and, in accordance with Kress (2010), linked to a multimodal approach. The ideational function, representing experiences and meanings about actions, states and events in the world through the use of semiotic resources, was used to analyze how teachers and students in their musical meaning-making represented actions linked to reflection in feedback situations. Here, the analyses concerned who did and said what in the interrelation between the teacher and student. Based on the interpersonal function, with focus on how social relations as well as, in line with Baldry and Thibault (2006), attitudes and values are established, maintained, and specified between those engaged in the communication, the analyses aimed to capture how the teachers and students interacted and positioned themselves in feedback situations. To highlight the textual function, representing the formation of complex semiotic message-entities (Kress, 2010), the analyses concerned how the teachers and students, using musical, bodily, or linguistic resources, rhetorically organized and conveyed meaningful messages regarding opportunities to reflect in feedback situations. From this textual angle, the focus also was on how they, with use of body, language, and music performances, motivated and argued for their actions and positions. Based on these functional analyses, it became possible to identify contrasting discourses operating in the meaning-making feedback activities. This overall phase of the analyses was aimed to highlight the participants’ verbally, bodily, and musically communicated views of how to act and use reflections in feedback situations. The analyses were based on the view that discourses are produced in specific institutions (Kress, 2010) as “some aspect of reality from a particular point of view, a particular angle, in terms of particular interest” (The New London Group, 2000, p. 25), and thus conveyed by the participants. Together, these analyses resulted in varying feedback approaches, each highlighting how discourses concerning feedback linked to reflection possibilities are realized in music educational situations. Since the aim of the study is to explore opportunities for student reflections, the analyze is more focused on linguistic than bodily resources, which can be seen as a limitation of the study given the choice of a social semiotic theory and analysis method.

Research Ethics

The Swedish Research Council’s guidelines regarding information requirements, de-identification, voluntary participation, and consent were followed for both teachers and students. To challenge the researcher’s own assumptions and acknowledge confirmation bias, the analyses and results have been presented and discussed by other researchers at research seminars. In presenting the results, no statements or categories are attributed to the involved institution and participants. When a dialogue is cited, the participants are referred to as T (teacher) and S (student).

Results–Creating Space for Reflection

Two contrasting discourses operating in the feedback meaning-making related to reflection emerged in analyzing the video-documented lessons. The negotiating discourse emphasizes reflection possibilities, offering a large space for student self-reflection, whereas the controlling discourse emphasizes reflection constraints, offering little or no space for student self-reflection. Both discourses occur in each video-recorded lesson, realized in various ways by the teachers and eliciting various responses from the students, depending on the situation and on how semiotic resources such as instrument/voice, body, and/or language are used. These realizations are constructed as feedback approaches with a mix of verbal, bodily, and musically performed instructions, rationales, and expressions intended to help the students advance in their development processes. The feedback approaches concern space for conversation and exploration of musical aspects, as well as call for attention to and re-creation of teachers’ interpretations and instructions. The findings are structured around how the controlling and negotiating discourses are realized in these feedback approaches. In the following, the findings are illustrated by verbal excerpts, photographs, and musical scores. Four sequences from the third video-recorded lessons were selected, each representing the findings.

Providing Space for Conversation

The approach providing space for conversation emphasizes how the teachers create opportunities for the students to discuss various didactic or musical aspects in interaction with the teacher, reflecting on how to learn to play/sing the music. This approach appears in conversations between teacher and student, often starting with a question or statement formulated by either party. Sometimes the students talk about an aspect of or problem in the music played, and sometimes the teachers talk about some interesting aspects of the instrument, singing voice, or music itself. In both cases, they talk about and negotiate these issues together, with freedom for the students to reflect on how to make their own choices and find their own solutions. Figure 1 and the associated excerpt are taken from a double bass lesson in rhythmic improvised music, in which the student practices “walking bass.” After the student has tried to play a walking bass, the teacher points out that such walking basses can become static even when the chords are changing, and therefore need to be reviewed:

01 T: When they [i.e., chord] still change, you can try to get between them.

02 S: But I feel that it always becomes [plays bb, a, g], in any case, I have nothing else.

03 T: [plays bb, f#, g in the small octave].

04 S: [plays bb, f#, g] or

03 T: Yes.

04 S: [plays b, f#, g] or [plays b, d, g]

05 T: Yes.

06 S: Or [bb, a, g].

07 T: Exactly.

08 S: It also works quite well.

09 T: But you can also play [plays a bass line with chromatic movements up and down from bb].

10 S: Yes.

11 T: What has happened?

12 S: [reflects a few seconds] For the second chord I now really think, there you have G minor [pointing at a book on a chair].

13 T: Yes.

14 S: but it can be both [g major and g minor].

15 T: It can be both, so it doesn’t matter.

16 S: So [inaudible].

17 T: Yes [plays some notes], but it can be fine to have some opening variations.

18 S: Yes.

In the playing and speech-based dialogue with the teacher, the student reflects on how to play a walking bass sequence based on a certain series of chords. First, he has only one solution to this problem, but after hearing the teacher suggest a solution by playing alternative notes on her bass, the student transforms the teacher’s proposed notes into his own walking bass, developing the possibilities by presenting variations on these notes. This ideational meaning-making process is represented by using several semiotic resources, such as instrumental playing, hearing, and gazes, to see and hear the other person’s musical intention, as well as by verbal reflections, statements, suggestions, and confirmations regarding what and how to play. In the interpersonal interaction, the student claims space for his own reasonings and reflections on how to play a walking bass based on a certain chord sequence, while the teacher is positioned as a listening teacher, offering input in the form of a few words and some notes played, finally pointing out the importance of having some variations to play. The student’s discovery of several ways to play a walking bass related to specific chords, his verbal negotiations of different possible solutions, and the teacher’s confirmations led to new student insights into how to develop the walking bass. In other words, the textual function of providing space for conversation is here realized in a feed-forward situation, in which reflections are encouraged as a tool for further development. In this situation, the negotiating discourse is dominant, especially regarding the teacher’s approach to providing space for the student’s self-reflection, realized not only as a dialogue between teacher and student, but also as a self-reflective conversation with oneself. However, the teacher somewhat controls the situation by helping the student find ways to develop walking bass skills, but the freedom to reason about and negotiate one’s own learning dominates.

Providing Space for Exploration

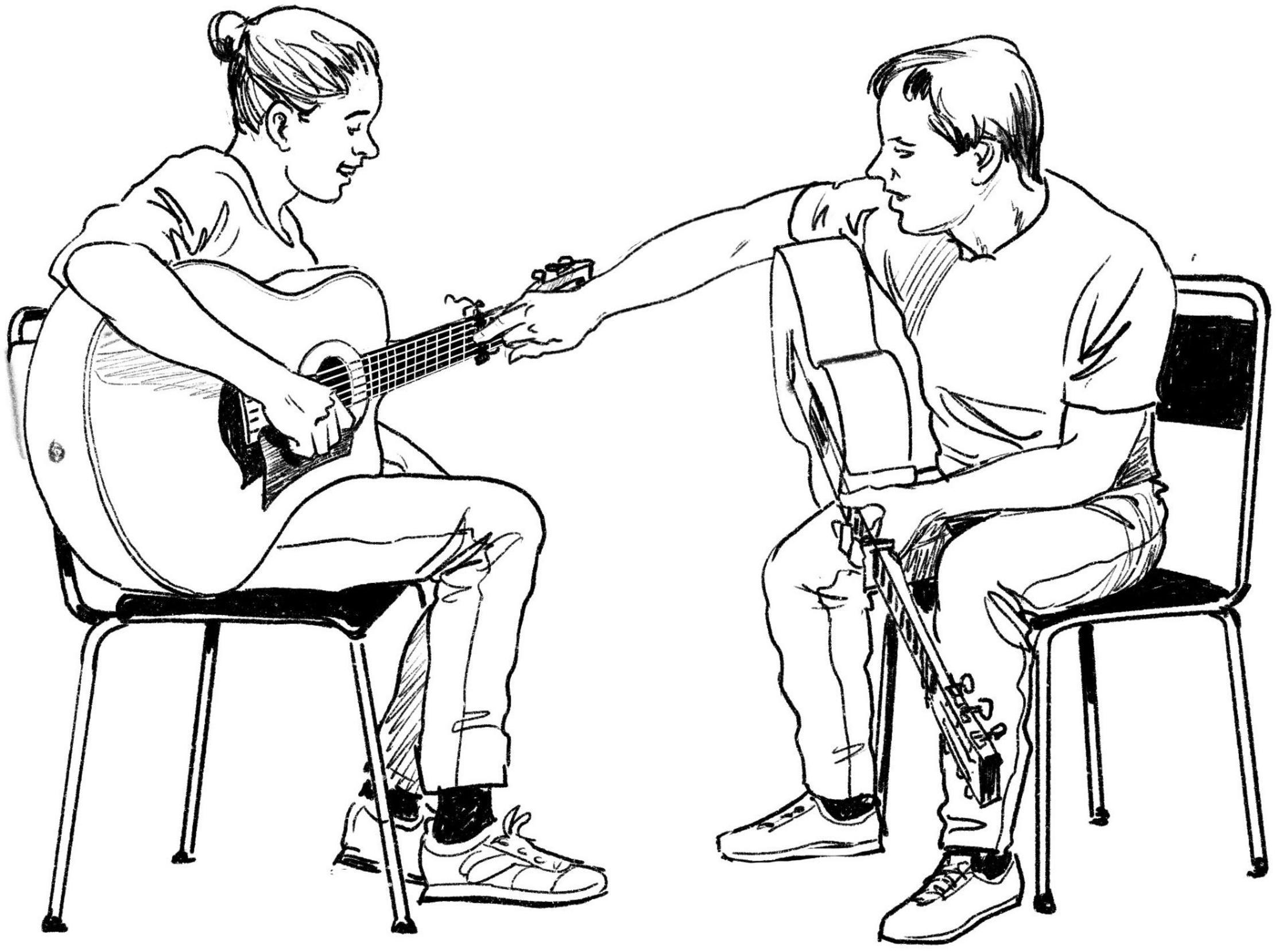

The focus on providing space for exploration concerns how the teachers provide space for students to creatively explore new aspects of their learning and musical performance processes. By first introducing certain musical elements, such as new chords or walking bass sequences, varying singing styles, or new possibilities for violin or guitar playing, and encouraging the students to develop or discover specific insights, such as a new instrumental technique, the teachers offer the students space to explore, reflect on and negotiate how different musical resources can be used. This can be done through joint playing or singing, such as improvised call-and-response sessions or having one party play the melody while the other plays the accompaniment. The teachers use semiotic resources such as speech, instrumental playing, gestures, and gazes to represent musical or instrumental features, and the students respond by developing the teachers’ representations into new performances. In this exploration process, the students’ freedom to reflect on and negotiate how to create their own solutions and interpretations is dominant. This approach is illustrated by Figure 2 and the associated excerpt from a folk music lesson, in which the activity starts with the teacher asking for a drone-based accompaniment on the three first strings on the guitar.

T: You play with these three strings now [points at the three first strings on the student’s guitar], and you can only touch this string [points at the student’s third string]. How would it sound if you accompanied me now in the A part of this [song]?

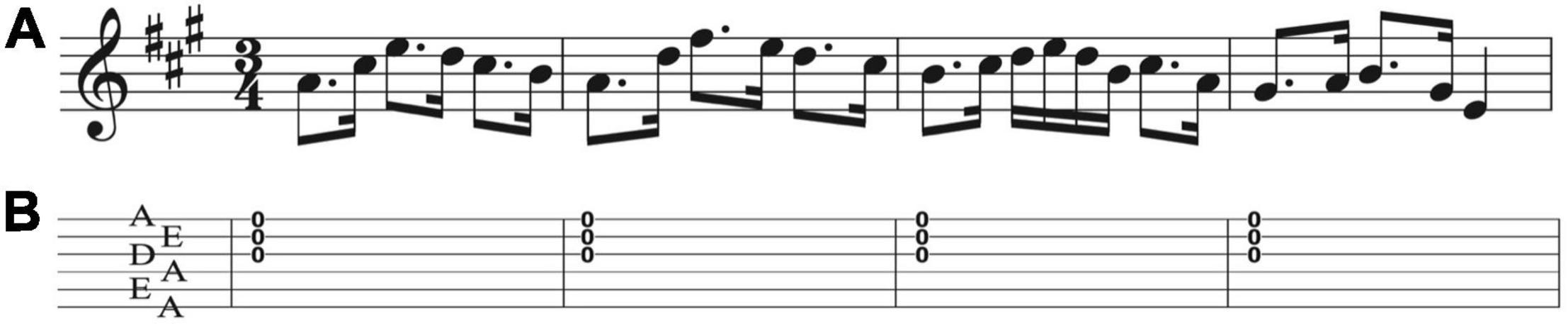

In Figure 3, the score shows four bars from the melody played by the teacher (A) and four bars with available strings and notes for the student’s drone-based accompaniment (B).

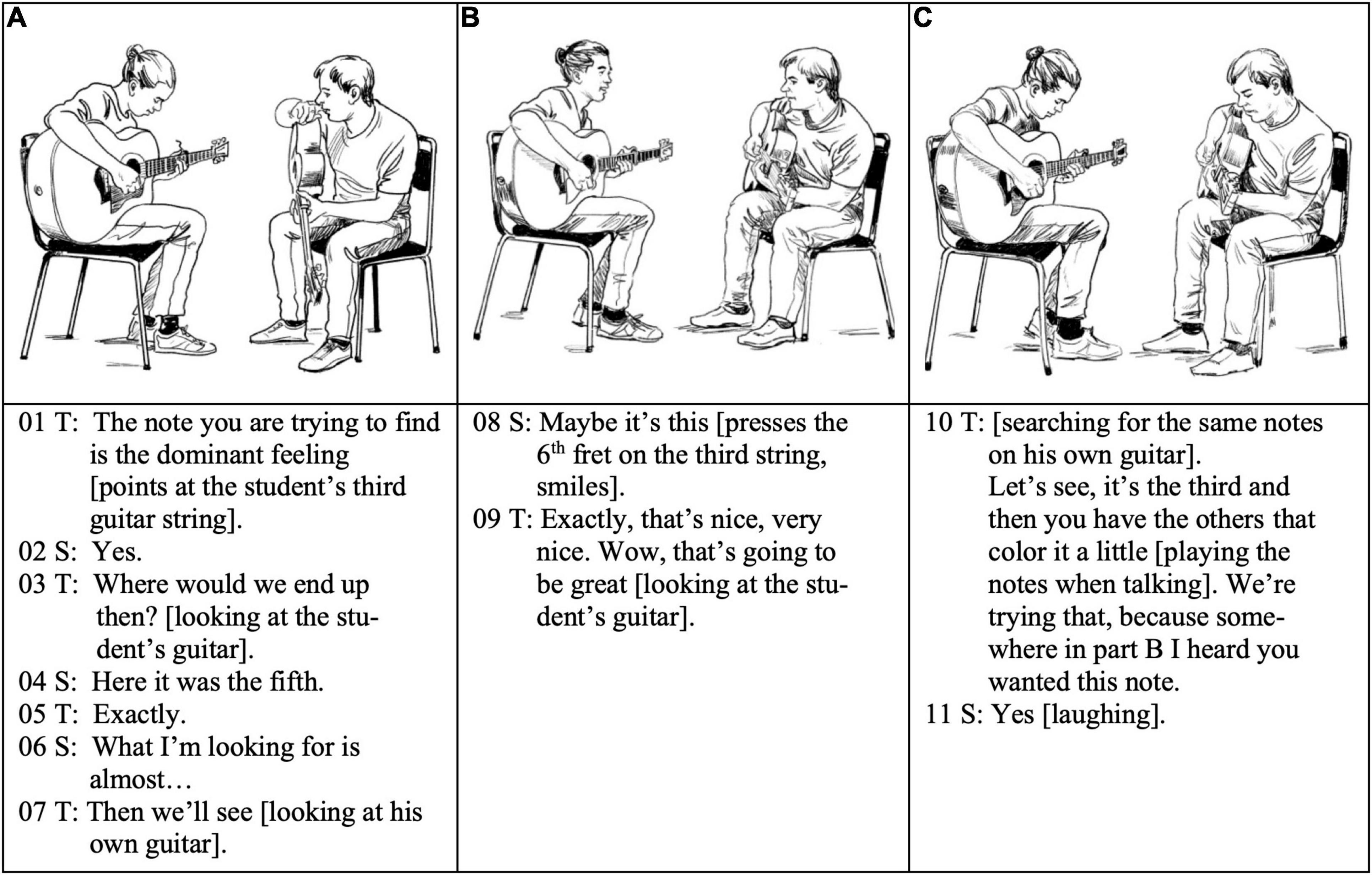

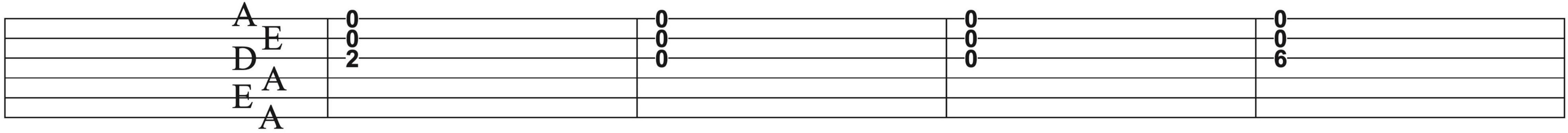

In these four bars and throughout the song, the student tries to find suitable notes on the third guitar string (D), while the two first strings (A and E) function as drones (capo tasto on the seventh string), providing rhythmic accompaniment in interplay with the teacher’s melodic playing. The student uses bodily resources such as gazes to pay attention to the teacher’s finger movements when he is playing the melody on the guitar. The student also uses hearing to listen to what the teacher plays and to explore which notes might be a suitable accompaniment for the teacher’s played melody. In this ideational exploration sequence, the student transduces his sight and hearing into the notes and rhythms he finds most appropriate for accompanying the melody. In the interpersonal interplay, the teacher assumes a rather low-key position when only playing the melody, waiting for, looking at, and listening to what the student can discover in his exploratory music making. However, in the last bar shown in Figure 3, the student could not find the note he was searching for despite active exploration. Figure 4 illustrates the dialogue after the exploratory playing session.

Since the guitars are tuned differently and use capo tasto on different frets, it becomes rather difficult for both the student and teacher to immediately understand what the other is playing, even though they are playing in the same written key. However, the teacher tries to help the student to find the desired note in the fourth bar, using gazes, gestures, and listening resources (turns 01, 03, and 07) to find out what the student is playing and wants to play. The student is still actively searching for the specific note (turns 04 and 06), using the same resources as the teacher, but eventually finds the note himself (turn 08), the major third in a dominant chord. Before playing together again, using the suitable notes (see Figure 5), the teacher confirms and praises the appropriate choice (turns 9 and 10).

All the activities in this session can be seen as constituting a creative and exploratory process, ultimately resulting in a functioning drone-based accompaniment. The ideational meaning-making can be described as a way, using several semiotic resources such as language-based instructions and questions as well as gestures, gazes, hearing, and guitars, to offer the student the opportunity and freedom to develop his musical performing via an exploratory and reflective approach. The interpersonal situation with the teacher’s support can also be seen as the negotiation of appropriate choices that lead forward to new insights and learning for both the student and teacher. Linked to the textual function of space for exploration, the negotiating discourse is dominated by the encouragement of exploration, reflection, and discussion realized in the musical meaning-making. Simultaneously, the teacher to some extent controls the situation by giving the student special conditions, such as specific strings appropriate for a specific melody.

Calling for Attention

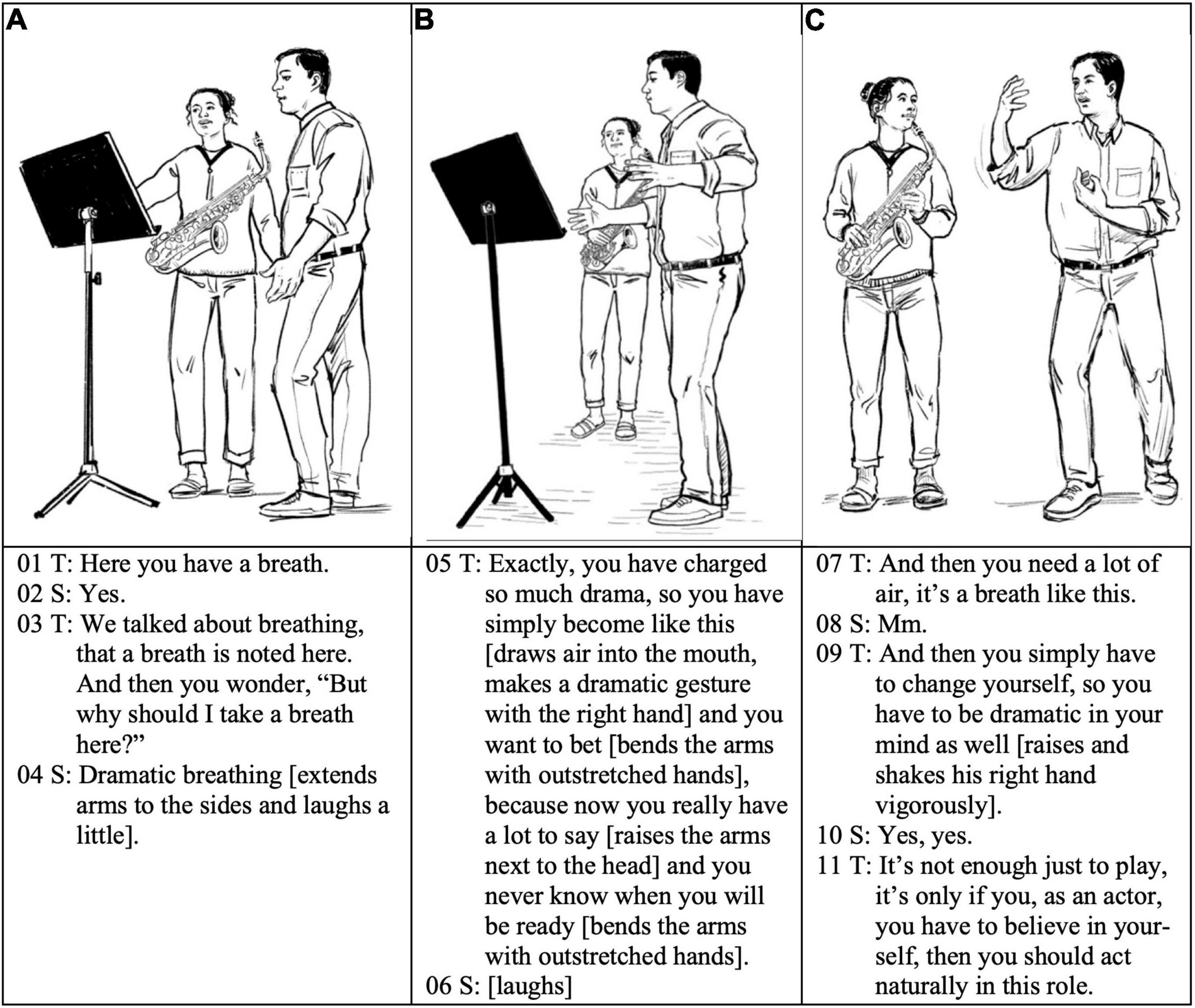

The approach of calling for attention sheds light on the teacher’s attempt to create conditions for the student to consider the teacher’s interpretations and instructions as well as implicit calls for responses or reflection. Here the teacher’s feedback is expressed not only through comments such as “fine” and “good” when responding to student performances, but also through instructions, stories, and experiences about how to work with the instrument or voice to perform the music. By using linguistic narratives, embodied expressions, dramatized interpretations, and directed gazes and gestures demonstrating special aspects, the teacher implicitly signals communication open to responses and further reflections about how to perform the music, as well as communication about how to reflect on further development issues. Sometimes the teacher seems to be waiting for verbal responses from the student, who sometimes answers with a short response or, most often, with no response at all, which results in a learning process of feed-forward based on controlling rather than negotiating. This construction is illustrated in Figure 6 and the associated excerpt from a classical saxophone lesson, which begins after the teacher has interrupted the student’s performance.

In this ideationally based scenario, the teacher draws attention to how to express the music more dramatically. He uses semiotic resources such as language as well as his arms and hands to illustrate how to feel the dramatic expression in the music (turns 05 and 09) and behave like a dramatic actor (turn 11), both in the deep breath before the actual phrase (turn 03) and to reinforce the desired musical expression. The student in turn responds to and reinforces the teacher’s comment about breathing through using gestures and speech and laughing happily (turns 04 and 06). Related to the interpersonal function, the teacher dominates the scene with his dramatic representations, while the student takes a low-key position by listening to the teacher, only responding with a few words. The situation can be described as an invitation from the teacher to the student to verbally reflect on and negotiate musical expression, and thus as feed-forward to further the development of the music meaning-making. However, as there are only a few student responses, here and throughout the lesson excerpt, the teacher’s instructions function more as a call for the student to pay attention to and perform the music in a way adapted to the teacher’s expressed views. With no negotiations or joint reflections about the music, the function of the teacher’s activities become controlling and guiding rather than emphasizing the freedom to reflect and negotiate. However, after the teacher’s instructions, the student’s responses are expressed in a sensitive performance of the music. The musically realized reflection and negotiation of the teacher’s instructions illustrate the student’s perception of how to play and develop the music, using the teacher’s feed-forward on how to dramatize the music as a starting point. The textual function, i.e., call for attention, is here permeated with both control, realized as the teacher’s instructions with no student verbal reflections, and to some extent with freedom to negotiate, realized as what are probably the student’s own reflections during the music meaning-making.

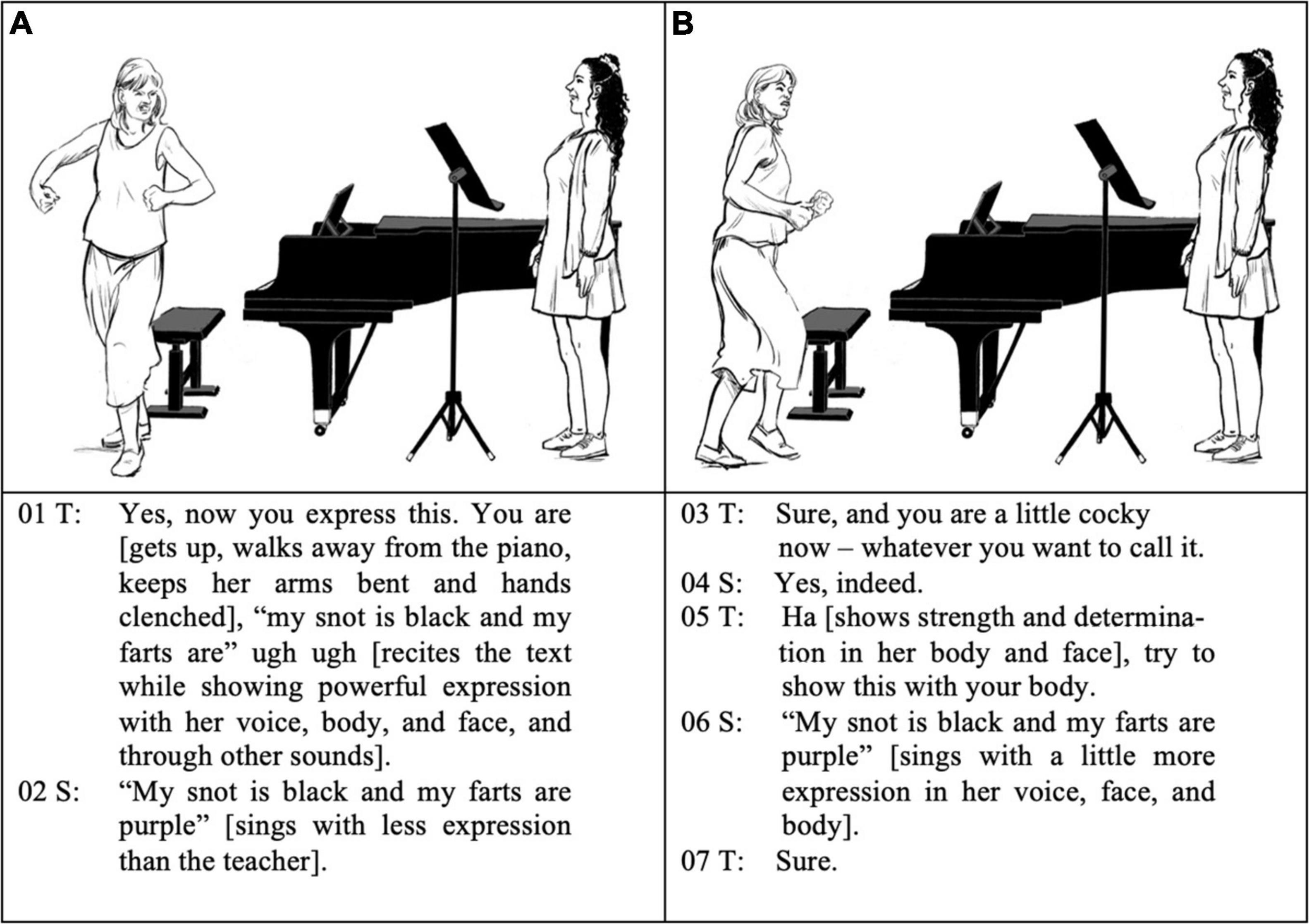

Calling for Re-creation

Calling for re-creation focuses on invitations to students to recreate their teachers’ instructions on how to learn and play the music. This construction is realized in different ways: through the teachers’ illustrative instrumental or vocal musical performances; by using language in verbal instructions and dramatizations; or by using the body in embodied dramatizations. The students respond through imitations and re-creations, by singing/playing, talking, or using the body as a resource. The construction is also realized by teachers and students playing or singing together, with the teachers playing/singing the desired notes, rhythms, and dynamics to illustrate how to play the music, while the students, in real time, recreate the teachers’ performances. These can be described as feed-forward situations in that they somewhat involve the students’ visual, auditory, and mental reflections on how to recreate the music, i.e., the students’ reflections through their own seeing, hearing, thinking, and embodied actions. In these contexts, the controlling discourse is dominant in that the teachers’ detailed instructions and their interpretations of the music are determinative. In the vocal lesson shown in Figure 7, the teacher is sitting at the piano asking the student to expressively interpret a very dramatic song about a poor woman, illustrating how to realize this.

01 T: And how do you say this to me now?

02 S: “Feel [i.e., smell] how I stink, rat sweat rotten fish” [singing].

03 T: Yes, you can mirror it in the face [keeps her hands close to her face].

04 S: I think that I’m a little happy that I smell so very bad.

05 T: Yes, a little like this [turns her face a little upward to the right]. Feel how I say it, again, “Feel how I stink” [turns her head a little to the left].

06 S: “Feel how I stink, rat sweat rotten fish” [reads the text, laughs].

07 T: Yes, you can exaggerate that character, not only in the speech, but I mean, “Feel how I stink,” can you, you [turns to an imaginary audience] should feel how I stink [dramatizes the text with her upper body and face].

Related to the ideational function, the teacher uses her language, body, and the face to present the lyrics expressively (turns 02 and 05): she exaggerates the character in the lyrics (turn 05), invites the student to do the same (turn 05), and emphasizes the importance of exaggerating and feeling the lyrics in the body when communicating to an audience (turn 07). At the beginning of the sequence, the student offers some of her own reflections (turn 04), but later she transforms the teacher’s body- and language-articulated text into her own verbal articulation (06). The teacher dominates the scenario, while the student is listening, waiting, and transforming. In the next sequence, 2 min later, the teacher is standing beside the piano (see Figure 8).

When inviting the student to interpret the song, the teacher exaggerates her articulation using some undefined semiotic resources such as words and facial grimaces (turn 01) and her whole body to represent the content of the lyrics, here in a rather cocky way (turn 05). The student responds by transducing the teacher’s dramatized spoken performance into her singing voice by performing expressively, although not as powerfully as the teacher (turns 02 and 06). Regarding the interpersonal function, the teacher positions herself as very active with powerful speech and embodied expressions, while the student applies a calmer approach when trying to express the song in a way similar to the teacher’s. The teacher’s activities using language and embodied expressions in these sequences can be described as a request to recreate what she is representing to the student. At the same time, there is space for the student to reflect on and negotiate how this re-creation should take a form appropriate for herself. However, whether or not the student reflects on her own is hard to discover in this sequence. It instead seems that the student is trying to imitate and thus re-create her teacher’s expressive interpretation. Here, feedback is, according to the textual function, constructed as leading toward the teacher’s obvious set goals for how to interpret the song, resulting in a controlling approach realized as a request for re-creation and reproduction.

Discussion

The article has highlighted how feedback in one-to-one tuition is regulated by two contrasting discourses, resulting in various ways of realizing feedback situations linked to reflection opportunities. While the negotiating discourse emphasizes opportunities for student self-reflection, the controlling discourse emphasizes restrictions on such opportunities. The feedback approaches realizing these discourses are described as providing space for conversation or exploration as well as calling for attention or re-creation, evident in all studied lessons. These feedback approaches are more or less regulated by control and freedom to negotiate related to reflection opportunities, since reflection is given more or less space in the teaching context. The first two approaches offer more space for reflection than do the other two, since the teachers explicitly allow space for reflection and the students actively take the opportunity to reflect during the lessons, searching for solutions and exploring new aspects. At the same time, the teachers to some extent control the situations by helping the students find appropriate ways to solve current problems. This controlling discourse is even more obvious in the approach calling for re-creation, in which students’ opportunities to reflect and make their own decisions about musical interpretation are limited by the teachers’ implicit request for imitation and reproduction. Likewise, calling for attention is constructed as a way of controlling the students’ musical interpretations and expression. However, an interplay between the two discourses is visible in this approach. Although there is some space for reflection in these two last approaches, the student reflection apparently takes its starting points in the teachers’ ideas about how to interpret, shape, and express the music, implicitly realized and shaped by the students in their own musical performances. Nevertheless, the two discourses are working side by side in each lesson, and used by all the studied teachers, obviously needed to achieve their considered goals of teaching.

The teachers’ representations of feedback dominated by the controlling discourse can be seen as strongly linked to the master–apprentice music tradition, in which copying (Burwell, 2013), learning inhibition (Gaunt, 2011), hierarchy, re-creation, and reproduction (Gaunt, 2011; Holgersson, 2011; Laes and Westerlund, 2018; Bull, 2019), as well as certain approaches to learning (Nerland, 2007; Christophersen, 2012) regulate the education. In this study, the teachers’ instructions and requests for the reproduction of demonstrated music-related aspects as well as their decisions about what has to be learned and communicated, and how, are in line with this tradition. That some students adopted a calmer, more reactive posture by listening, re-creating, and reproducing their teachers’ instructions, instead of demanding space in which to negotiate how to articulate and express the music can, according to previous reports of students’ confidence in teachers as musical experts (Gaunt, 2011; Holgersson, 2011), be seen as a result of this tradition. On the other hand, the present findings regarding the teachers’ calls for conversation or exploration dominated by the negotiating discourse, in which the students’ reflections, explorations, and independence are in focus, can be related to later institutional curricula and government requirements regarding reflection (Swedish Code of Statutes [SFS], 2009, 2010) as well as equality, democracy, and lifelong learning (SOU, 2001), requirements considered necessary for teacher students to become well-functioning teachers. Previous reported improved reflective practices (Johansson, 2013; Barton and Ryan, 2014) can be seen as a result of these requirements. In the present study, these requirements were found to be met by the teachers, who allowed space for students to reflect on, comment on, or address specific issues during the lessons, and they could be met by the students themselves by taking space in which to reflect on various issues. Instead, some of the students adopted a calmer and more passive posture, making few or no verbal statements.

Is it possible to create more space for student reflection and independence in group teaching? With group instrumental/vocal lessons, the teachers probably have greater latitude to create an open atmosphere and avoid previously reported secretive and private teaching interactions (Gaunt, 2011; Burwell, 2012; Carey et al., 2013; Burwell et al., 2019) in favor of joint discussion and reflection between teacher and students. Since collaborative teaching situations reportedly encourage and benefit teacher students’ learning and reflection (Latukefu and Verenikina, 2016; Lebler, 2016; Chapman Hill, 2019), such situations would probably increase teacher students’ opportunity to make space for their own reflections.

The fact that reflective practices and collaborative dialogues are considered to contribute to, improve and secure students’ learning (Johansson, 2013; Barton and Ryan, 2014; Carey et al., 2016; Esslin-Peard et al., 2016; Hakkarainen, 2016; Lebler, 2016; Georgii-Hemming et al., 2020; Johansson and Georgii-Hemming, 2021) reinforces the importance of encouraging students to independently reflect on their own learning processes and development opportunities as well as on musical interpretations, problem solving, exploration, and new discoveries. Such competencies is needed to increase teacher students’ opportunities, in their future work as teachers in elementary, secondary, and upper secondary schools, to realize curriculum goals regarding their students’ reflections on their own experiences, as described by the Swedish National Agency for Education (2013). To achieve this, teachers should, in line with Black and Wiliam (2009) statement regarding the importance of discussions between teachers and students, and according to the requirements of reflections set forth in the Swedish Code of Statutes to a greater extent provide space for students’ capacity to act so that they can become reflective and independent learners. A collaborative work, where teachers and students reflect and solve problems together (Creech and Gaunt, 2012) as well as collaboration between students resulting in deeper interaction and engagement (Johansen and Nielsen, 2019), where student can think reflectively about their development (Gaunt et al., 2012) can probably further develop teacher students to be independent reflective teachers helping their future students to reflect.

Although this study was limited in scope, its findings regarding feedback approaches and interaction patterns regulated by either the controlling or negotiating discourse generate knowledge of both potentials and limitations regarding reflection opportunities in instrumental/vocal teaching, appropriate for the field of music didactics and for music teacher students’ professional development. In this sense and with reference to Gaunt (2011) and Hakkarainen (2016), the study also contributes to discussions of how to enable teachers to reflect critically on their own teacher–student relationships and of how reflection opportunities can become part of staff development, building teamwork for student coaching instead of teaching in isolation. Here, reflection-on-action (Schön, 1984) could act as a possible tool for higher education instrumental and vocal teachers to watch and self-reflect on their own videotaped lessons, aiming to identify more opportunities to engage their students in reflective thinking. If such reflections are made collaboratively with colleagues, the reflections can, with regard to Schön, enable the teachers to restructure their understandings of how to act, criticize themselves and test other colleagues’ suggestions.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available upon request to the corresponding author, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

RS-J contributed to the design and implementation of the study, the analyses, and the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by The Teacher Education Board, Karlstad University, Sweden.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank the teachers and students who gave their time to carry out this study, as well as the illustrator, Lars-Åke Pettersson, who created illustrating pictures from the video-recorded lessons.

References

Baldry, A., and Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis. London: Equinox Publishing Ltd.

Barton, G., and Ryan, M. (2014). Multimodal approaches to reflective teaching and assessment in higher education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 33, 409–424. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2013.841650

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 21, 5–31. doi: 10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

Bull, A. (2019). Class, Control, and Classical Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190844356.001.0001

Burwell, K. (2013). Apprenticeship in music: a contextual study for instrumental teaching and learning. Int. J. Music Educ. 31, 276–291. doi: 10.1177/0255761411434501

Burwell, K., Carey, G., and Bennet, D. (2019). Isolation in studio music teaching: the secret garden. Arts Hum. High. Educ. 18, 372–394. doi: 10.1177/1474022217736581

Carey, G., Bridgstock, R., Taylor, P., and Grant, C. (2013). Characterising one-to-one conservatoire teaching: some implications of a quantitative analysis. Music Educ. Res. 15, 357–368. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2013.824954

Carey, G., Scott Harrison, S., and Dwyer, R. (2016). Encouraging reflective practices in conservatoire students: a pathway to autonomous learning? Music Educ. Res. 19, 99–110. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2016.1238060

Chapman Hill, S. (2019). “Give med actual music stuff!”: the nature of feedback in a collegiate songwriting class. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 41, 135–153. doi: 10.1177/1321103X19826385

Christophersen, K. (2012). Rhythmic music education as aesthetic practice. Nordic Res. Music Educ. 13, 233–241.

Cranmore, J., and Wilhelm, R. (2017). Assessment and feedback practices of secondary music teachers: a descriptive case study. Vis. Res. Music Educ. 29:6.

Creech, A., and Gaunt, H. (2012). “The changing face of individual instrumental tuition: value, purpose, and potential,” in The Oxford Handbook of Music Education, eds G. E. McPherson and G. F. Welch (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199730810.013.0042

Crispin, D. M. (2021). Looking Back, Looking Through, Looking Beneath. The Promises And Pitfalls Of Reflection As A Research Tool. Knowing And Performing. Artistic Research In Music And The Performing Arts (s. 63–76). Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. doi: 10.14361/9783839452875-006

Esslin-Peard, M., Shorrocks, T., and Welch, G. F. (2016). Exploring The Role Of Reflection In Musical Learning And Performance Undergraduates: Implication For Teaching And Learning. Art and Humanities as Higher Education, Vol. 15, Special Issue Aug 2016. Available online at: http://www.artsandhumanities.org/ahhe-special-issue-june-2016

Gaunt, H. (2008). One-to-one tuition in a conservatoire: the perceptions of instrumental and vocal teachers. Psychol. Music 36, 215–245. doi: 10.1177/0305735609339467

Gaunt, H. (2011). Understanding the one-to-one relationship in instrumental/vocal tuition in Higher Education: comparing student and teacher perceptions. Br. J. Music Educ. 28, 159–179. doi: 10.1017/S0265051711000052

Gaunt, H. (2016). Introduction to special issue on the reflective conservatoire. Arts Hum. High. Educ. 15, 269–275. doi: 10.1177/1474022216655512

Gaunt, S., Creech, A., Long, M., and Hallam, S. (2012). Supporting conservatoire students towards professional integration: one-to-one tuition and the pontential of mentoring. Music Educ. Res. 14, 25–43. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2012.657166

Georgii-Hemming, E., and Westervall, M. (2010). Teaching music in our time: student music teachers’ reflections on music education, teacher education and becoming a teacher. Music Educ. Res. 12, 353–367. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2010.519380

Georgii-Hemming, E., Johansson, K., and Moberg, N. (2020). Reflection in higher music education: what, why, wherefore? Music Educ. Res. 22, 245–256. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2020.1766006

Hakkarainen, K. (2016). “Mapping the research ground: expertise, collective creativity and shared knowledge practices,” in Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education, eds H. Gaunt and H. Westerlund (Abingdon: Routledge), 13–26.

Hallam, S. (1998). Instrumental Teaching. A Practical Guide to Better Teaching and Learning. Oxford: Oxford Heinemann Educational.

Hallam, S., and Bautista, A. (2012). “Processes of instrumental learning: the development of musical expertise,” in The Oxford Handbook of Music Education, eds G. E. McPherson and G. F. Welch (Oxford: Oxford University Press), doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199730810.013.0040_update_001

Halliday, M. (2013). Hallidays’ Introduction To Functional Grammar. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203431269

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Holgersson, P. H. (2011). Musikalisk Kunskapsutveckling I Högre Musikutbildning – En Kulturpsykologisk Studie I Hur Musikerstudenter Förhåller Sig Till Kunskap I Enskild Instrumentalundervisning Musical Learning And Development In Higher Music Education: A Cultural-Psychological Study Of Performance Students’ Way Of Relating To One-To-One Tuition. Doctoral dissertation. Stockholm: KMH-förlaget.

Johansen, G., and Nielsen, S. (2019). The practicing workshop: a development project. Front. Psychol. 10:2695. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02695

Johansson, K. (2013). Undergraduate students’ ownership of musical learning: obstacles and options in one-to-one teaching. Br. J. Music Educ. 30, 277–295. doi: 10.1017/S0265051713000120

Johansson, K., and Georgii-Hemming, E. (2021). Processes of academization in higher music education: the case of Sweden. Br. J. Music Educ. 38, 173–186. doi: 10.1017/S0265051720000339

Jordhus-Lier, A. (2018). Institutionalising Versatility, Accommodating Specialists. A Discourse Analysis Of Music Teachers’ Professional Identities Within The Norwegian Municipal Schools Of Music And Arts. Doctoral dissertation. Oslo: The Norwegian Academy of Music.

Kress, G. (2009). “Assessment in the perspective of a social semiotic theory of multimodal teaching and learning,” in Educational Assessment in the 21st Century, eds C. Wyatt-Smith and J. J. Cumming (Dordrecht: Springer), 19–41. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-9964-9_2

Laes, T., and Westerlund, H. (2018). Performing disability in music teacher education: moving beyond inclusion through expanded professionalism. Int. J. Music Educ. 36, 34–46. doi: 10.1177/0255761417703782

Latukefu, L., and Verenikina, I. (2016). “Expanding the master–apprentice model: tool for orchestrating collaboration as a path to self-directed learning for singing students,” in Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education, eds H. Gaunt and H. Westerlund (Abingdon: Routledge), 101–109.

Lebler, D. (2016). “Using formal self- and peer-assessment as proactive tool in building a collaborative learning environment: theory into practice in a popular music programme,” in Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education, eds H. Gaunt and H. Westerlund (Abingdon: Routledge), 111–121.

Nerland, M. (2007). One-to-one teaching as cultural practice: two case studies from an academy of music. Music Educ. Res. 9, 399–416. doi: 10.1080/14613800701587761

Sandberg-Jurström, R. (2009). Att Ge Form Åt Musikaliska Gestaltningar. En Socialsemiotisk Studie Av Körledares Multimodala Kommunikation I Kör Shaping Musical Performances. A Social Semiotic Study Of Choir Conductors’ Multimodal Communication In Choir. Doctoral dissertation. Gothenburg: Art Monitor, Gothenburg University.

Sandberg-Jurström, R. (2016). Kroppsliga representationer för musikaliskt meningsskapande i sångundervisning. Bodily representations of musical meaning-making in singing lessons. Nordic Res. Music Educ. 17, 167–196.

Schön, D. A. (1984). The Reflective Practitioner. How Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

SOU (2001). The Government’s Official Investigations Den Öppna Högskolan The Open University 2001/02:15. Stockholm: Ministry of Education and Research, Sweden.

Swedish Code of Statutes [SFS] (2009). The Higher Education Ordinance. Issued: 4 February 1993 1037. Stockholm: Ministry of Education and Research, Sweden.

Swedish Code of Statutes [SFS] (2010). The Higher Education Ordinance. Ordinance Amending The Higher Education Ordinance (1993:100). Issued: 4 February 1993 541. Stockholm: Ministry of Education and Research, Sweden.

Swedish National Agency for Education (2013). Curriculum For The Upper Secondary School. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

Keywords: feedback, self-reflection, one-to-one instrumental/vocal lesson, specialist music teacher education, social semiotic theory, video recordings

Citation: Sandberg-Jurström R (2022) Creating Space for Reflection: Meaning-Making Feedback in Instrumental/Vocal Lessons. Front. Educ. 7:842337. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.842337

Received: 23 December 2021; Accepted: 24 February 2022;

Published: 14 April 2022.

Edited by:

Cheryl J. Craig, Texas A&M University, United StatesReviewed by:

Lilian Simones, The Open University, United KingdomNatassa Economidou-Stavrou, University of Nicosia, Cyprus

Copyright © 2022 Sandberg-Jurström. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ragnhild Sandberg-Jurström, ragnhild.sandberg-jurstrom@kau.se

Ragnhild Sandberg-Jurström

Ragnhild Sandberg-Jurström