Resilience among Children Born of War in northern Uganda

- School of Law, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

The literature on children born of conflict-related sexual violence, or Children Born of War (CBOW) is dominated by accounts and perceptions of suffering and risks that they experience both during and after armed conflict. In contrast, this article focusses on nuanced experiences of CBOW after suffering adversities. The study applies the culturally sensitive revised 17-item Children and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-R) to 35 CBOW conveniently sampled from a population of those born to former forced wives of the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) and another population born between 1993 and 2006 as a result of sexual violence perpetrated by cattle raiders in northern Uganda. Following the analysis of the CYRM-R scores, eight participants representing different quartiles, different scores on the relational/caretaker and personal resilience sub scales were identified to take part in a subsequent semi-structured interview process. The aim was to examine how CBOW in northern Uganda demonstrate resilience, the factors that influence their resilience experiences, and what it means for the broader concept of integration. Overall, CBOW are not merely stuck in their problems; past and present. Rather, findings indicate CBOW are confronting the realities of their birth statuses, and making the best use of their resources and those within the wider environment to adapt and overcome difficulties.

Introduction

Whereas, the field of youth and adolescents affected by armed conflict has started registering theoretical and empirical studies on the concept of resilience (e.g., Cortes and Buchanan, 2007; Betancourt and Khan, 2008; Baum et al., 2013; Zuilkowski et al., 2016), there is very little resilience research relating to Children Born of War CBOW. Rather, existing literature on the subject of CBOW (e.g., Carpenter, 2007, 2010; Ladisch, 2015; Apio, 2016; Lee et al., 2021), primarily deals with trauma-centered research focusing on negative impacts of violence, stigma and discrimination experienced in post conflict zones. This approach limits attention on other dimensions of the experiences of CBOW leaving out many aspects of their wellbeing. As Zuilkowski et al. (2016) observed bad experiences associated with armed conflicts do not mean the people are “doomed to suffer the consequences interminably” (p. 65). This article contributes to a fuller appreciation of the complexity of post-conflict experiences by exploring resilience in CBOW and the factors that might shape and influence expressions of resilience, given their respective contexts in Lango, northern Uganda.

The article applies the understanding of resilience as “the qualities of both the individual and the individual's environment that potentiate positive development” (Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011, p. 127). To this end, resilience can be located “in the interactions between individuals and their wider social ecologies” (Clark, 2021, p. 1). Theron (2019), on her part presses further, by arguing that resilience is co-facilitated by individuals and the systems of which the individuals are a part (p. 327; see also Theron et al., 2021). In other words, the wider material and socio-cultural environment is just as important as the individual in the production of resilience. Important to note is that constant variations in the social-ecological environments, including availability of resources and differences in power relations between individuals and groups, reflect on the nature of resilience, rendering it a “dynamic and fluid process” (Henshall et al., 2020, p. 3,598), see also Bottrell (2009).

The complex, unstable and “fluid” nature of resilience the literature speaks about is further reflected in the lack of a “universally accepted methodology for operationalizing and measuring resilience empirically” (Alessi et al., 2020, p. 570). See also Christophe et al. (2020, p. 2), with different measures developed over the years to measure different things. Some of them are culturally sensitive, and demonstrate resilience by measuring the levels of interaction between individuals and their material and social cultural environments. One such scale of measurement, is the measure applied in this study; the abridged version of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure developed by the Resilience Research Centre (2018)—referred to as the Child and Youth Resilience Measure—Revised (CYRM-R). The measure is comprehensively presented in the methods section.

Subsequent sections of this article review the existing scholarship regarding CBOW and resilience, including the relatively sparse body of literature, and provide an overview of the case study and background of the conflicts linked to the participants. This is followed by a summary of the methodology the study used. The article then presents and discusses the results and reflections from the CYRM-R dataset and the associated qualitative interviews.

Resilience: Adversity and positive outcomes

Scholars have associated stressful experiences such as illnesses, loss of loved one, serious accidents, wars and associated ills with negative outcomes (Mochmann and Larsen, 2008). Often cited is that these stressful experiences can lead to behavioral, psychological and emotional outcomes that are negative (e.g., Aldwin, 1994). Commonly cited are negative outcomes like Post Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD), depression, distress, all of which are well-addressed in the literature (e.g., see Masten et al., 1999; Calhoun and Tedeschi, 2001; Bostock et al., 2009; Aburn et al., 2016). But there has also emerged a great debate about positive outcomes in the aftermath of adversity. These “positive outcomes” have been referred to variously, including as: “Post traumatic growth, stress-related growth, benefit-finding, perceived benefits, thriving, positive by-products, positive psychological changes, flourishing, positive adjustment, positive adaptation” (see: Tedeschi and Calhoun, 2004; Ramos et al., 2016). In this article, these “positive outcomes” are referred to as resilience.

The last two decades have seen a major shift in the understanding of resilience. Instead of earlier ideas that centered resilience on individual psychological traits, which influenced “an individual's ability to ‘bounce back' or return to a normal state following adversity” (Hoegl and Hartmann, 2021, p. 456), the definitions have now embraced social ecological approaches that position resilience as a process or outcome co-facilitated by individuals and the systems or social ecologies of which the individuals are a part (Luthar et al., 2000; Ungar, 2011; Wright and Masten, 2015; Theron, 2019, p. 327). In other words, resilience is now understood as resulting from the interrelation and interconnections between individuals and their wider environments. This means that resources available in the wider environment such as family and community support, access to health resources and economic opportunities are central for victims-survivors' coping and adaptation.

A social-ecological environment can therefore be viewed as a melting pot of resilience resources (rather than an empty space), with individuals as part of the embedded material and social-cultural factors that are constantly interacting. This further suggests that resilience as a process or outcome depends on more factors than those that lie within the individual. Rather, both the intra-and inter-personal factors within the wider social ecology are crucial in co-facilitating production of, or hindering resilience. These include familial, communal and societal factors (Roper, 2019). These factors have been linked to variations in how individuals demonstrate resilience, with some more resilient in a given situation than others (Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011, p. 127). Often cited, particularly with respect to children and youth, are temperament, gender, physical health, age, developmental stage, sense of humor, self-esteem, locus of control, family support, parental discipline, spirituality, communal support, intelligence, coping techniques, psychological state, sense of direction or mission, adaptive distancing, androgynous sex roles and realistic appraisal of the environment (Green et al., 1981; Werner and Smith, 1992; McAdam-Crisp, 2006, p. 463). Moreover, studies already offer that social support and family harmony are major factors that shape self-esteem in adolescents (e.g., Han and Kim, 2006), further underscoring the importance of the social-ecology in the shaping of resilience (see also Ungar, 2011; Clark, 2021). In other words, a social-ecological approach to resilience, which this article applies, enables a holistic understanding of the contributing factors of an outcome. It offers a theoretical framework for understanding the dynamic interplay among individuals, groups, and their socio-physical environments (Stokols, 1996, p. 283).

Resilience studies in the field of armed conflict

The literature on resilience in people affected by war and armed conflict have gained traction in the last decade (e.g., McAdam-Crisp, 2006; Klasen et al., 2010; Ferrari and Fernando, 2013; Zuilkowski et al., 2016; Dixon, 2018; Clark, 2021). However, the focus has largely been on former child combatants, survivors of sexual violence, and survivors of genocide with minimal focus on CBOW. More accurately, an online search of resilience-related literature revealed a handful of sources on CBOW, including Schwartz (2020)'s literary work on children born during WW II in Europe; a recent study of CBOW in Bosnia, Rwanda and northern Uganda in which the authors argue for the use of survivor-centered approach to, among others, broaden “the remit of the victim category beyond primary harm, to consider structural and cultural harm” (Alessia et al., 2021, p. 342). Another explores how post conflict initiatives helped “children born in captivity” in northern Uganda overcome extreme adversity and hardship by “engaging with youth within multiple, interactive environments rather than targeting solely the individual” (Dixon, 2018, p. v), and yet another (Meaghan and Denov, 2021) focuses on the experiences of children born of genocidal rape in Rwanda, arguing for “greater recognition of the shared or relational nature of resilience” (p. 1).

Whereas, these sources demonstrate growing interest in the field, they do so from different understandings of the idea of resilience, which in itself, is a contextually sensitive concept. Thus, the idea of resilience as applied by Schwartz (2020) on CBOW in Europe during WW II was different from that studied by Meaghan and Denov (2021) in Rwanda, and Dixon (2018) and Alessia et al. (2021), in northern Uganda. It has been questioned whether the meaning of the term resilience as applied by scholars and practitioners working on and within post-conflict communities differs from the understanding of the term by the local populations to which they are applied (e.g. Allen et al., 2021; Bimeny et al., 2021). The current article takes note of this, by focusing on CBOW living in Lango society, and whose births were linked to different conflicts. It further draws on studies that view children (including children of survivors of conflict-related sexual violence) as “crucial protective resources for those around them” (Clark, 2021, p. 4), to re-focus attention on CBOW as co-creators of resilience within the social ecology. As the literature notes, until recently, most of the information about these children was embedded within narratives and discourses that explained the resilience of their mothers (e.g., Smith, 2005; Veale et al., 2013). This may be due to dominant approaches that consider protection and understanding of children as being linked to the protection and understanding of their mothers.

Of interest in the current article are questions about how familial attachments and communal connections work for the resilience of a group (CBOW) globally associated with stigma, rejection, and discrimination. These questions are further occasioned by findings in studies of non-CBOW categories which emphasized the role of family, community and other societal factors. For example, resilience scholars offer that a youth's coping ability may be enhanced by an attachment to his/her guardian (e.g., McAdam-Crisp, 2006, p. 466). Others like Garbarino (1995) argued that youth can cope with the stress of social upheaval if they retain strong positive attachments to their families, and if parents continue to project a sense of stability, permanence, and competence to their children (p. 44). Additionally, suggested that a strong bond between caregiver and the child, social support from teachers and peers, and a shared sense of values are important. Moreover, Kirschenbaum (2017), studying children in the Soviet Union during WWII, stressed the “importance of social supports and cultural resources in collective efforts to manage the trauma of war” (p. 538). Families, and the attachment to guardians and support of teachers cited above are some of the contextual (social-cultural) and individual factors that influence whether youth will overcome barriers and “resume positive life trajectories, or struggle to reintegrate into their families and communities” (Zuilkowski et al., 2016). These contextual and individual factors have been referred to in various resilience studies as protective factors that enhance resilience (e.g., Peltonen et al., 2014). Peltonen et al. actually examined resilience levels and protective factors of Palestinian students attending school during war and found that children with high resilience levels had better friendships compared to the traumatized group with low resilience levels. Applied to CBOW: What bonds and relationships exist? Would such bonds and relationships have similar impacts? In other words, this article contributes to exploring how CBOW in northern Uganda express resilience, the factors that influence their resilience experiences, and what insights into resilience mean for the broader concept of integration.

The case study: Conflicts and CBOW in northern Uganda

The Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) conflict in northern Uganda lasted from 1987 to 2008, and was the single most violent conflict in Uganda's post-independence history (e.g., Jeffery, 2011, p. 84–86; Refugee Law Project, 2014, p. 149–153; Opio, 2015; Allen et al., 2020, p. 663–683). The conflict was characterized by gross human rights violations and crimes against humanity including; plundering property, abduction of thousands of children and young adults, maiming of civilians and massacres (Refugee Law Project, 2014; Opio, 2015, p. 151–152). Whereas, Acholiland and its immediate border communities were at the epicenter of the conflict, the war gradually ate up large chunks of northern Uganda, to cover West Nile, Lango, and Teso in eastern Uganda. “Two million people in the Acholi sub region, 200,000 people in the Teso (eastern Uganda) sub region, 41,000 people in West Nile and 33% of the population in the Lango sub region were displaced due to the conflict” (Refugee Law Project, 2014, p. 133).

At least 60,000 civilians were abducted between 1986 and 2008, including at least one in three adolescent boys and one in six adolescent girls (Carlson and Mazurana, 2008, p. 4, 16). Once abducted, the individual would undergo “a well-designed process of brutalization” including forcing them under “threats of death and torture to take part in beatings and killings of children who collapse under the burden of the workload, who disobey orders, or who attempt to escape” (Akhavan, 2005, p. 406, see also p. 283). As part of indoctrination, abducted people were specifically forced to commit atrocities often on their own families and communities so they would find it hard to leave the LRA (Pham et al., 2009, p. 9–23). As documented in several accounts (e.g., Akello et al., 2006, p. 229; Stout, 2013, p. 27), atrocities associated with the LRA made it hard for ex-combatants to reintegrate in their pre-war communities once they left the LRA.

At least 10,000 of the abducted girls and young women became forced wives and had children out of their experiences between 1998 and 2004 (Akello, 2013, p. 149–156).1 Scholars argue that the LRA used forced marriage for various purposes, besides sexual services, with “wives” typically performing domestic roles, cooking and washing for their LRA “husbands,” and giving birth to and raising children (e.g., Carlson and Mazurana, 2008, p. 45; Baines, 2014, p. 405). But sexual violence perpetrated by the LRA also targeted civilians during raids in northern Uganda (e.g., Ojiambo, 2005, p. 10; Pham et al., 2007, p. 18; Arieff, 2010, p. 7).

Scholars argue that the marriage-like relationships that Kony nurtured in his movement contradicted the local norms and institutions regulating sex, marriage and motherhood in peacetime northern Ugandan communities, many of which became the return communities of the women and their children (e.g., Apio, 2016, p. 174). Returning mothers and their children faced a lot of stigma and found it more difficult to reintegrate compared to other ex-combatants (e.g., Carlson and Mazurana, 2008, p. 5; Buss et al., 2014, p. 75; Apio, 2016, p. 178). In other words, stigma has been central in determining the experience and extent of reintegration of survivors and their children (Buss et al., 2014, p. 75; Opio, 2015; Akullo, 2019). Mothers with children were isolated from the rest of society because of the biological association of the children with the LRA (Esuruku, 2011, p. 30; Buss et al., 2014, p. 45). Most of these women were “shunned by their families and labeled as ‘bush women' by their communities”, forcing them to abandon their homes to live in the suburbs of Gulu where many earned a living as prostitutes or alcohol brewers (Esuruku, 2011, p. 30).

Beyond the LRA's abductions and sexual violence, northern Uganda has also been the scene of a less publicized non-state conflict of cattle rustling since 1987 (e.g., Refugee Law Project, 2014, p. 145; ICPALD, 2019).2 Whereas studies have focused on the millions of herds of cattle lost to raids, and subsequent disarmament processes, accounts of gross human rights violation on victim communities across the region have rarely been documented. Sexual violence remains a casualty in this regard. Recent studies however suggests that countless children and women were raped, abducted, and sometimes killed (e.g., Seymour et al., 2022). Whereas many were kept for short periods of time during the course of the raids, some were taken into Karamoja and assimilated into families against their will, and later forced to “marry.” Although their case is not well-known in the field of conflict-related sexual violence, their experiences of stigma, and discrimination, among others, have started appearing in studies (Akello et al., 2006; Mukasa, 2017). Available literature indicates that besides the long term consequences of the sexual violence suffered (such as fistula, bullet wounds, stigma and rejection) survivors also grappled to raise children they had as a result of sexual violence. For example, a recent study identified a 45-year-old woman who had escaped from a forced marriage with her 5 out of 6 children (the eldest had reportedly joined a group of raiders and was absent at the time of her escape) back to her natal family in Otuke district in east Lango in 2012. She had been abducted as a child in 1987. A recent research impact intervention based on a documentary (“The Wound is Where The Light Enters”)3 also included children linked to cattle raids in Lango.

Central to the understanding of the experiences of CBOW (and particularly those linked to the LRA) is the local argument by Lango elders that abduction and forced marriage contradicted Lango's jural rules of attaining motherhood and affiliation of a woman's offspring (Apio, 2016). Affiliation status determined the residential options and access to cultural, social and economic resources associated with either of the biological parents. For example, at the time of the study, the largely patriarchal Lango still affiliated offspring of a married woman to her husband's as long as the offspring was conceived within the marriage (even if the pater was different). Offspring of women conceived before or after a divorce would still affiliate to the mother's patriclan. Affiliation of male children opened doors for these children to automatically benefit from patrilineal assets—such as land and livestock, were the child male. In return, his labor, achievements and losses would be associated with the patriline to which he/she was affiliated. Where, she or he accused of causing death to a person from another patriclan, then the responsibility for meeting blood compensation would fall on the membership of her/his patriclan. Such provisions and liabilities raised the stakes for CBOW, considering the extent of “damage” their fathers were associated with in the social-cultural environment—e.g., abduction, forced marriage, killings and displacement of entire communities, and for the cattle raiders; violent cattle and other livestock raids, and forceful affiliation of abductees as family members in Karamoja, forced scarification and other bodily tribal markings on abductees, forced marriage, and impregnation.

By applying a social-ecological approach to resilience therefore, the study directly targeted the status of CBOW affiliation, how they performed in terms of resilience and what resources mediated their performances.

Methodology

The study applied a combination of quantitative and qualitative measures in a two-phased fieldwork approach. In the first phase, the author administered a questionnaire comprising of demographic section and the culturally sensitive revised 17-item Children and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-R) (Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011; Liebenberg et al., 2012). The aim was to obtain scores and measure resilience in CBOW. In the second phase, the author drew on the results from the analysis of the CYRM-R scores to identify eight participants to take part in a subsequent semi-structured interview. The eight participants represented different quartiles and had different scores on the relational/caretaker and personal resilience sub scales. This section provides a summary of description about the study instruments, sampling of study participants, study procedure, and how the analysis was conducted.

Study instruments

The mixed methods study, implemented in two phases, involved the application of a questionnaire and an interview guide; all specifically tailored to suit the context and the aim of the study.

Phase 1: The questionnaire

The questionnaire had two sections. The first section was made up of questions aimed at generating demographic information. These included; age/year of birth, sex/gender, marital status, having a child(ren), ethnicity, education level, employment/profession, and who was the head of household. The second section comprised of the CYRM-R scale. The CYRM-R is a self-report measure of social-ecological resilience suitable for use with individuals aged 10–23 (Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011), but it can be applied to older adults depending on a researcher's assessment of the abilities of respondents (Resilience Research Centre, 2018, p. 23). The CYRM-R measure, made up of two subscales, typically consists of 17 items and can be scored on a 3-point Likert scale. The subscales are; personal resilience (10 items), which considers intrapersonal and interpersonal items; and caregiver/relational resilience (seven items), which relates to characteristics linked to the important relationships shared with a primary caregiver, a partner or family (Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011). These subscales are however linked as they both rely on individual wider social environment to influence their resilience. All of the 17 items on the measure are positively worded, and the analysis relies on simple summary of responses. This 3-point version is scored using options of “No” (1), “Sometimes” (2), and “Yes” (3).

The CYRM-R measure enables individuals to easily comprehend items and give scores based on their own reflections. This was particularly appropriate because the study sample was part of a population various studies have described as one of the most neglected and marginalized in northern Uganda, and globally (Carpenter, 2007; Apio, 2016; Lee et al., 2021). In addition, respondents were drawn from locations deep in rural northern Uganda (Otuke and Oyam districts) with low levels of literacy (UBOS, 2014). For reliability, the questionnaire was translated and back translated into Lango (Luo), the local language widely spoken by the local population in the study sites.

Phase II: Semi-structured interviews

The interview stage drew on the suggested questions for “contextualizing measures” (see: CYRM and ARM User Manual 2.2, page 8; Resilience Research Centre, 2018), to generate an interview guide for the study. The questions were:

- What do I need to know to grow up well here?

- How do you describe people who grow up well here despite the many problems they face?

- What does it mean to you, your family and your community when bad things happen?

- What kinds of things are most challenging for you growing up here?

- What do you do when you face difficulties in your life?

- What does being healthy mean to you and others in your family and community?

- What do you and others you know do to keep healthy? (Mentally, physically, emotionally, or spiritually)

The interviews were audio-recorded, and a consent form was used with options for seeking consent of a guardian in case of a minor, or if an adult participant asked a witness to observe the informed consent process. The informed consent forms were based on the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST) format, and translated (and back translated) into Lango. The study was approved by the northern Ugandan-based Lacor Hospital Research Ethics Committee (LHIREC) (Ref. no: 0189/08/2021).

Sampling

The study conveniently sampled 35 CBOW, aged 15–28 years. This sample was identified through contacts with female survivors of CRSV who were known to the community based paralegals associated with the local NGO Facilitation for Peace and Development (FAPAD) based in Lira. 20 of the CBOW were drawn from Otuke district in east Lango, at the border with east Acholi and Karamojong, and were all fathered by cattle raiders. 15 other participants, all fathered by the LRA were drawn from Oyam district, in North West Lango at the border with west Acholi. The youngest (CBOW) participant in this study was born in 2006 and the oldest in 1993 (15–28 years old). The study thus involved respondents who were technically not yet adults (15–18 years), raising ethical issues regarding consent. For those whose ages ranged from 15 to 18 years old, the study designed an additional consent form for their parents or guardians. Additional provisions on the respondents' consent form (irrespective of the age range) included the right to withdraw from the study at any time during the completion of the questionnaire as well as during the interview phase. None of the 35 respondents in the study lived or had contact with their birth fathers or birth fathers' relatives.

Administering the questionnaire

The questionnaire was administered with the help of two local research assistants conversant with the language and geographical context from September to October 2021. To ensure that the varying levels of participants' literacy was taken into consideration, the research assistants read the questionnaire out aloud to each participant in a quiet and secure location of his/her choice. The research assistants each worked individually with the respondents to ensure they understood each of the 17 items in the CYRM-R measure, but also to comply with the minimal ethical standards for researching persons associated with sexual violence—a sensitive subject, particularly in contexts where studies associate conflict-related sexual violence with high levels of stigma (e.g., Carpenter, 2007; Apio, 2016; Lee et al., 2021). On average, each questionnaire took ~20 min to complete compared to the standard average of 5–10 min advised by the Resilience Research Centre (2018). This was attributed to the demographic questions/items added to the CYRM-R scale.

Semi-structured interview

The author conducted four interviews, and one of the research assistants who had taken part in administering the questionnaire conducted the remaining four interviews. All of the interviews were conducted in Lango (a Luo dialect widely spoken in the study location) and audio-recorded upon taking consent of the participants. The interview recordings were then transcribed, and translated into English for further analysis.

Analysis

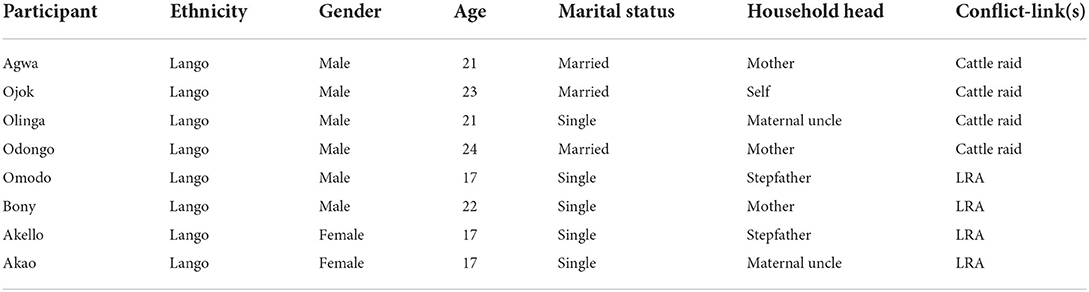

Analysis of data happened in two phases. In the first phase, the focus was on the demographic characteristics of the respondents, and how each of them performed on the CYRM-R scale. Total scores for each participant (N = 35) for all 17 items were calculated, against the standard minimum score of 17 and maximum score of 51 (Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011). Consequently the analysis considered comparing CBOW who posted high scores to low scorers, by placing overall scores into quartiles from lowest to highest in order to identify eight participants from different quartiles to take part in a qualitative investigation for potential reasons for these differences (see Table 1 for a summary of demographic information for the eight participants).

The second phase focused on the responses generated during the semi-structured interviews. First, the audio responses were transcribed and translated into English. The author then manually coded the responses and analyzed emerging patterns to support, by triangulation (Gretchen et al., 1985, p. 633; Dawadi et al., 2021, p. 28), the findings related to the CYRM-R scores above. All of the respondents were anonymized. Pseudonyms have been used to refer to participants in the presentation and discussion of study findings.

Results

The following are the findings of the analysis of the scores posted by 35 respondents on the CYRM-R scale, and the semi-structured interviews with eight participants (two female and six male) whose scores represented different quartiles on the CYRM- R scale.

Demographics

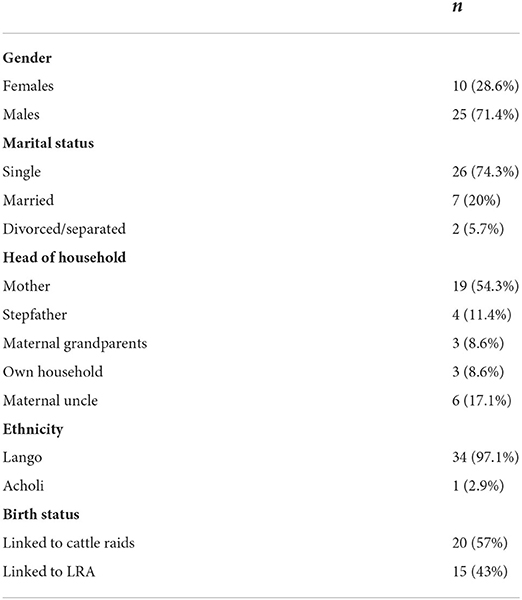

The mean age of respondents was 19.69. Majority of them were males (71.4%, n: 25) compared to females (29.6%, n: 10). Of these, 57% (n: 20) had their births linked to cattle raids, while 43% (n: 15) were linked to LRA sexual violence. 1 (2.9%) respondent identified with the Acholi ethnicity, while 34 (97.1%) respondents identified with Lango ethnicity (see Table 2 for a summary of the demographic characteristics of CBOW who took part in the study).

At the time of the study, majority of the respondents were single (74.3%, n: 26), followed by those that were married (20%, n: 7), and those that had separated or divorced (5.7%, n: 2). Out of the 35 respondents in the study, 54.3% (n: 19) lived in households headed by their mothers, while 17.1% lived in their mothers' brother's households. The remaining respondents either lived in households headed by a stepfather (11.4%, n: 4), maternal grandparents (8.6%, n: 3), or own household as married men (8.6%, n: 3).

The overall total, means and standard deviations in resilience scores were calculated. As regards resilience overall scores, the lowest on the CYRM-R scale was 28, which was well above the standard minimum overall score of 17, and the highest was 48 compared to the standard maximum overall score of 51. The results showed a total overall average resilience score of 38.31 (SD = 5.098). In addition, participants aged 19 and above had higher resilience scores (M = 21.38, SD = 1.360) compared to those aged 15–18 years old (M = 17.19, SD = 1.360). Those whose birth were linked to cattle raids had higher resilience scores (M = 39.35, SD = 5.194) compared to respondents whose births were linked to the LRA (M = 36.93, SD = 4.788). As regards sex, individual male participants indicated more positive association with resilience enhancing factors on the CYRM-R scale compared to female respondents. That is; on average male respondents answered “sometimes” to the 17 items (which are considered in this study as resilience enhancing factors for CBOW) compared to female respondents who on average provided the answer “no.”

CBOW's understanding of resilience

Whereas, the study applied a standardized measure of resilience (CYRM-R), it was important for it to put into perspective what the participants meant by resilience—and to further project that meaning onto their respective CYRM-R scores. The study did this by asking participants to describe people who grow up well in spite of suffering adversity. Some of their responses included the following;

…people who grow up well here even when they face problems are known by their good relationship with other people, and the extent to which they support each other. They are known as God-fearing people (interview with Omodo, 21 January 2022).

Olinga (20 January, 2022), on his part stated that:

…they are courageous and strong because they have gone through many challenges but still managed to handle life in a way that makes them continue surviving.”

Another, Ojok, explained that:

“they are people with strong blood, because they survived the hardship while in the bush” (20 January, 2022).

By referring to good social relationship, and support networks that individuals draw on, participants underscored the importance of connections and community in their understanding of resilience. However, they also drew attention to the importance of personal attributes such as faith or belief, bravery and strength, among others. Important to note is that their responses were not necessarily worded in the same way local population explained resilience, but were descriptive and rooted in their individual everyday experiences of how the local social-cultural environment interacted with each of them. This is crucial because another study that targeted non-CBOW survivors of conflict-related sexual violence (also linked to the LRA and cattle raids) in the same locality (some of whom were mothers of the CBOW who participated in the study for this current article) reported heavy use of metaphors to refer to resilience.4 For example, the older non-CBOW generations used “roc”—a term denoting the processes of ecdysis that refers to the shedding of old skin in arthropods (e.g., Cheong et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019), and the fallowing of arable land (as explained by Lango elders in that study) to sum up the dominant meaning of what they understood as resilience. As a survivor in that particular study (with non-CBOW) stated; “the life we are living now that the war is no longer here is, I can say, a life that has ‘roc' {renewed}. We have peace. We sleep in the house. We dig {the land}. We do things that we can because there is now no war. We rest, and that's why I say life has ‘roc' [renewed].”5

Although the current article did not explore the nuanced meaning of resilience among CBOW any further, the descriptive as opposed to metaphoric language used by the older non-CBOW generations could be explained by the extent of socialization of CBOW in the Lango social-cultural environment. In other words, CBOW may not have been able to readily comprehend nuanced languages of their new contextual environments because either they had spent longer periods growing up outside of Lango (e.g., in Karamoja or in the LRA), or were still young at the time of the study, or both.

Co-creating resilience in different sub contexts

The results showed that individual CYRM-R items contributed differently to the overall scores, even where respondents had same scores. For example, four respondents, each with total scores of 36, which is also one of two modes, did not always draw uniform scores from the same items. On the contrary, there was a mix of contributions across all the 17 items that make the CYRM-R. The difference in how CBOW score similar items suggests that access to and interactions with resilience-supportive (or protective) factors in their respective environments differ for every CBOW and that different factors contribute differently in the co-creation of resilience. This suggestion also mirrors the different experiences CBOW had, depending on whether one's birth was linked to the LRA or to the cattle raiding conflicts.

As the results above showed, participants whose birth were linked to cattle raiding-related sexual violence had higher resilience scores compared to those whose births were linked to LRA sexual violence. The skewedness of the results in favor of participants in Otuke/linked to cattle rustling, majority of whom are male (n = 18), is also reflected in the results on sex above, where male participants performed better compared to female participants (majority of whom were linked to the LRA and hailed from Oyam). Whereas the analysis could not determine the reasons for this variation, participants in the cattle raiding conflict were older in ages compared to those associated with the LRA. And, as the results further showed, those aged 19 years and older (15 of whom were linked to cattle raids and only 5 to the LRA) showed higher resilience levels compared to those aged 15–18 years (11 of whom were linked to the LRA and only 4 to the cattle raids). Moreover, there can be a possibility of resilience factors at different levels of the social-cultural environment behaving differently in Otuke compared to Oyam, even though both districts are located in Lango; and how CBOW linked to the LRA are perceived and “accepted” compared to those linked to cattle raids. These differences are important in mediating how resilience can be understood in different (sub) contexts associated with CBOW, and for the design of integration policies and programmes.

Variations were further emphasized by all eight interviewees. For example, interviewees identified how family and community differentially related with them as important factors in their lives. Within the family, most CBOW identified mothers as particularly significant, while others associated more with grandparents. Some relied more on other members of their mothers' extended families, particularly mothers' brothers, their agnates and their children. Relationships with stepfathers were also singled out as significant.

Often, as will be discussed in subsequent sections, participants spoke about their birth fathers when referring to stigma and denial of right to critical resilience resources like land—an important resource controlled by male elders of respective patriclans in Lango. The absence of fathers who could have guaranteed, by affiliation, their access to such resources suggested that birth fathers were an important (but missing) resource that could have enhanced the co-creation of their resilience.

Often, the prevailing social-cultural environment shaped the nature of bonds associated with CBOW. For example, when asked how his life was growing up, 21-year old male participant Olinga who had an overall score of 45 (second highest) on the CYRM-R scale stated, among other things:

Life did not start well for me, because I was rejected by my relatives when I returned from captivity. Many of them were scared of me due to my being a male child. They thought my existence would bring land wrangles among the family members since there were already many boys at home.

Interviewees also identified factors in both the immediate and broader community they lived in as significant in their lives. These included peers and friends, school community (students and teachers), mother's patrilineage and religious leaders. These were sometimes labeled as supportive and sometimes as non-supportive, demonstrating how resilience factors may work differently at different times and for different CBOW. The significance of these bonds and relationships was demonstrated by how interviewees apportioned their experiences of access and denial to familial and communal resources they perceived as important in enhancing their livelihoods. For example, 17-year-old female participant Akello who was one of the three respondents with the second highest overall CYRM-R score of 45, explained the role her teachers played in her life;

While at school, my life was made difficult by some students. They would backbite me and laugh at my being born {a CBOW}. When I reported this to my teachers, they encouraged me and asked me to ignore those bad words. Often, the teachers gave them a punishment so they could stop disturbing me in school.

Studies already showed that stigma directed at CBOW often stem from their perceived birth status, and interacts with already existing intersectional issues such as gender, disabilities, local cultural jural rules and practices, and poverty to continuously diminish opportunities for integration (e.g., Apio, 2016; Denov and Lakor, 2017; Neenan, 2017; Ruseishvili, 2021). The significance of familial and communal bonds and relationships to resilience in CBOW is explored further in the section on relational factors below.

Further analysis suggests that all eight participants interviewed found personal agency, which they variously stated came in form of skills, a positive mind, a peace of mind, spirituality and being industrious, essential in helping CBOW define, access and interact with these familial and communal bonds and relationships in a mutually beneficial way. In this way, CBOW and their wider environments are seen co-creating or co-facilitating prospects of integration.6 For example, 20-year-old Agwa, a male participant in Otuke, explained that his mother gave birth to him and his younger brother during her captivity in Karamoja. But upon escaping, she resettled them in her parents' homestead at Otuke. He further explained that upon the death of his widowed grandmother, members of his mother's patriclan (mother's brothers), expelled him, his brother and his mother from the land. He added that it was his industriousness that gave him a new home:

A good Samaritan who owned a farm in the community came to our rescue and we are now living on his land. We normally work for him for free, like farming, selling his animals, and visiting his children in school so he can continue providing shelter for us.

Another, 17-year-old male participant Omodo who lived with his mother, stepfather and their two children in Oyam, and had the second lowest overall score on the CYRM-R scale at 29, explained that he started his own rice-growing farm on a wetland and was looking forward to accumulating capital to start a better life elsewhere. He added that the wetland was a resource nobody owned, compared to his stepfather's land, which he had no chance accessing or ever owning.

Another, 23-year-old male participant Ojok explained that he undertook a joint brick-making business with two friends for a number of years and used the money to solve his family's needs and pay his school fees. He further stated he bought a piece of land to move his mother and brother upon their grandparents' death when his mother's brothers sent them away from the family land. Not only was Ojok able to put his industriousness to good use, but he did it in concert with youth from his local community. Together with them, Ojok transformed his agency into a means of breaking down boundaries that separated him as a CBOW, and other youth in his community. In other words, his example demonstrated that CBOW were able to co-construct important connections and relationships within their own communities to enhance their wellbeing.

These examples show the important role CBOW's agency play in their own integration. The concept of resilience enables CBOW to demonstrate their role in co-creating their own integration in their wider environments. Further, the examples suggest that individual CBOWs depend on their own material and social-cultural environment to reinforce resilience. Subsequent discussions of the analysis will therefore draw on personal and relational aspects of CBOW's experiences to elaborate on findings for their full effects.

Relational factors

In this study, and based on inputs from interviewees, the concept of family included mother, mother's natal family members, stepfathers, and, in the case of an interviewee who was married or had a partner, his or her own marital family. The local extended family notion sometimes incorporated members of a mother's entire patriclan. For example, some male interviewees singled members of their mothers' patriclans as being responsible for denying them right to land. However, interviewees also often spoke about important connections and relationships with the material and wider social-cultural environment with which they interacted. But the significance of mothers in CBOW lives in particular, often positioned mothers as common denominators in how interviewees viewed and positioned themselves within the prevailing social-cultural environment. The analysis has therefore taken into consideration these contextual issues in defining aspects of relational resilience for CBOW in this study.

Further analysis suggests that respondents relate differently with resilience “enhancing” or “protective” resources within their respective social-ecological environment. An average CBOW has stronger resilience-supportive bonds within the familial environment compared to bonds with other entities in the wider community. Generally, interviewees identified and associated mothers, mother's natal families, and mother's marital family as important reference points within their respective families. These reference points are where bonds forged can work to co-create resilience in CBOW. Weakened or ruptured bonds can limit, interrupt, suspend or prevent interactions and relationships that are enabling for resilience in CBOW.

The nature of relationship and how a CBOW interacted with the household head, was important in determining the extent of available resources CBOW had at their disposal. Important was that the “available resources” for households headed by mothers were extremely limited at the backdrop of a largely patriarchal community that relied majorly on customary land for its economic wellbeing, and this affected the extent of resilience resources participants could drew from. For example, participant Ojok who scored lowest at the overall CYRM-R scale level, stated that his mother was thrown out by her brothers when his grandparents died, interrupting the lives of Ojok and his family. Ojok, his mother and his brother were only able to resume their lives when they located another piece of land, which was barely enough to meet their farming needs (interview with Ojok, 14 November 2021).

Co-creating resilience in CBOW

Further analysis of the individual items on the CYRM-R scale returned a mean score of 3.0 for the item “Getting an education is important to me,” followed by a mean score of 2.77 for the item “I know how to behave/act in different situations…” These findings not only correlate with other studies that identify access to education as an important priority for CBOW, as expressed by mothers (e.g., Janine Clark, 2021, p. 1,080), but add voice to interviewees' responses which suggested getting an education changed their lives. For example, interviewee Olinga (with second highest score of 45) who was at a teachers' training institute stated that not only had people in his community offered him a leadership role, but he was able to apply to become a head teacher at a primary school (interview with Olinga, 20 January 2022). Importantly, interviewees associated vocational skills and knowledge with more opportunities to improve on their economic wellbeing. For example 21 year old Agwa stated;

I had a friend called [] who taught me how to weld and I was earning small amount of money from it…with the little [skill] I learnt in welding, I took my mother's advice to move to Lira and I took an additional course to advance my skills. I now have a certificate in metal fabrication and I work in a better place (interview with Agwa, 19 January 2022).

However, majority (six interviewees) stated they were either still in primary school or had dropped out. Lack of school fees was often cited.

The importance of Agwa's experience was not only shown in the skills he had gained and put to use, but how he acquired it. By referring to a friend as the source of his training in welding, Agwa demonstrated the importance of connections and relationships with resources in his wider environment and how they helped him to co-produce and utilize skills to enhance his wellbeing.

On another note, lowest scores on the CYRM-R scale were for the item “My friends stand by me when times are hard,” followed by “I am treated fairly in my community.” Importantly, these scores (as with overall CYRM-R scores cited above) correlate with interviewees' perception of how they related with other people in their communities. A common denominator most cited was stigma, an important resilience-diminishing factor which differentially influenced the lives of interviewees.

Whereas all eight interviewees complained about stigma linked to their birth, each of them identified and perceived it differently. Some stated that they experienced stigma differently from different individuals within their respective families, while others associated it with different people in their wider communities. Still, most interviewees experienced stigma from within their families, neighborhoods and schools. These differences in perceived stigma from within families, neighborhoods and communities more broadly demonstrate complex layers of factors that interact with each other to define the wellbeing of a CBOW. Moreover, they also demonstrated clarity on the bonds that CBOW perceived as important in their integration.

For example, 17-year-old Akello whose birth was linked to the LRA cited stigma as defining her relationship with members of her community. She stated;

My life has not been good in the community. Majority of community members abuse me that I am the product of Kony {LRA leader} and that because of that, I do not deserve to stay in my village. Others say I am fatherless and this makes me feel so sad (interview with Akello, 22 January 2022).

Another, 17-year-old male participant Omodo, whose birth was also linked to the LRA sexual violence, and had a total score of 29 (second lowest), complained about on-going stigma, stating:

In the community, they treat me bad like I am not one of them. Some of them tell me to my face that I do not belong to that place and that I should look for my home. Sometimes, I hear them whispering that my stepfather is not my real father, and that I am a bastard. This makes me feel out of place and I begin regretting why I was born (interview with Omodo, 21 January 2022).

The narrative about stigma was not any different for interviewees whose births were linked to cattle rustling. For example, 21-year-old Agwa (whose younger brother was also fathered by a cattle rustler) elaborated their experiences, which can be associated with most CBOW. He stated:

In the village, we also face a lot of stigma from both relatives and community members. For example, when my brother and I are walking around the village, people point at us while saying “those are children of the Karamojong,” and this makes us feel out of place. But there is nothing we can do.

For participant Ojok, stigma was felt all around. He stated,

“I and my brother are called ‘ogwangogwang' [wild cats] by our mother's relatives and other people in the community where we live. They keep saying we are a waste of resources because it is just a matter of time before we steal all of the cows and head back to Karamoja” (interview with Ojok, 20 January 2022).7

On her part, 17-year-old Female participant Akao, whose birth was linked to the LRA sexual violence and had PR score of 19, emphasized that stigma was likely to remain in her life. She stated, “...even if you grow up well, removing that name [stigma] from the minds of people is very difficult” (interview with Akao on 14 November 2021). With such a high score Akao, who found being referred to as “Kony's child” stigmatizing, on the one

hand, demonstrated the complexity of associating resilience with CBOW who continue living in their mothers' natal families and communities—particularly those that experienced the conflicts. On the other hand, her example showed that whereas CBOW continue to experience adversity, they are not stuck in it.

These testimonies further demonstrate just how complex, and intricately linked to the wider social-cultural environment, CBOW's perceptions of their personal resources were, both as children and as young adults in northern Uganda. Whereas, perceived stigma indicated the extent of disconnections and ruptures in bonds and relationships CBOW had with individuals in their wider environments, at another level stigma clarified who was available to support the co-facilitation of resilience in CBOW. This was especially pronounced where such individuals also had control over resources perceived by CBOW as important in their lives, such as land, money for school fees and emotional support. These individuals were important in the unlocking of such resources. The health or strength of bonds was felt in the extent to which those bonds were essential in facilitating protection or access to protective resources for CBOW. For example, interviewee Omodo stated that his most debilitating experience was the refusal of his stepfather to meet the cost of his education, which forced him to drop out of school. Omodo further stated that he had come to terms with the possibility that his stepfather would not allow him access to his lands. As such Omodo stated he was investing in rice growing on a swampy patch of land that belonged to no one in particular with the aim of accumulating funds to start a new life elsewhere. Bonds of kinship and community were therefore important in either enhancing or diminishing resilience in CBOW. By linking perceptions of stigma to the nature and health of bonds of kinship and communal relationships, CBOW demonstrated that factors associated with their personal resilience did not always act independently. In other words the factors linked to individual CBOW agency and those linked to relationships tend to interact with each other to enhance or diminish resilience in CBOW, suggesting they were best addressed concurrently for the benefit of CBOW.

Legacies of harms on protective factors

Interviews suggested that bonds and relationships in the wider environments were more often than not also struggling with the effects of harms suffered during conflict, which tend to impact on how they relate with CBOW. For example, interviewees identified relatives who were themselves struggling with stigma and rejection, alcohol abuse, poverty and therefore inability to meet basic needs at home. For example, 24-year-old Odongo whose birth was linked to cattle rustling stated that, “My mother was always weak, and I keep thinking it was the effect of the alcohol she abused. She simply took too much alcohol and it was bad for us” (interview with Odongo, 20 January 2022). This example shows how CBOW's experiences of resilience-influencing factors are linked to other people and in the broader social ecology.

Interviewees also demonstrated how harms they suffered during armed conflict, not necessarily linked to their birth, influence their experiences of resilience. These included abduction, physical and mental health-related issues. For example, 24-year old Odongo whose birth was linked to the sexual violence associated with cattle rustling, complained about a chronic health problem he sustained when he was abducted in childhood by the LRA. He states:

Another problem that I am going through is severe pain in my foot. There is something which keeps growing inside my foot, and I do not understand what it is. It started when I roamed the bush as a child abducted by the LRA. At times when it grows big and protrudes, I can cut it with a razorblade, and sometimes I limp or walk like a lame person. I feel I need to get an operation so that I can walk well but I do not have the money to go to the hospital (interview with Odongo, 22 January, 2022).

Odongo's complaint of a crippling chronic foot pain has significant implications for the contribution of both his personal resilience (as it affects his mobility and involvement in physical activities at home and in the community), and relational resilience as physical disability is often a source of stigma and rejection in most rural communities in Lango (e.g., HRW, 2010). Moreover, Odongo also complained about stigma linked to his birth, and a mother who abused alcohol. His, like for many other CBOW, was therefore a constellation of resilience-challenging factors linked to his war experiences, and layers of other everyday social-cultural and contextual factors.

Still, within the same conflict, participants had different experiences, often influenced by a number of other factors such as gender, age, marital status of mother before and after abduction, absence or presence of maternal grandparents, etc. Important to note is that the two conflicts happened in communities that have similar social-cultural contexts - with varying degrees of patriarchal under/overtones. In some cases the CBOW mothers were sexually abused by both LRA and cattle raiders. Also, in one of the cases, a CBOW whose birth was linked to sexual violence during cattle raids was abducted by the LRA for a period of time. Whereas there are differences even within same group, the study did not dig further. Rather the study aimed at assessing whether CBOW demonstrate resilience to begin a debate on what might explain the findings. This was therefore a limited study.

Conclusion

The scores on the CYRM-R scale demonstrated by the respondents showed that CBOW were not merely stuck in their problems, past and present. The scores demonstrated variation in resilience; with some participants demonstrating high levels of resilience in the face of significant adversities. The findings indicate CBOW were confronting the realities of their birth status, and making the best use of their resources and those within their wider environments to adapt and overcome difficulties.

Interviewees further showed the extent of resilience enhancing resources available, what these resources were, where they were located, and how harms suffered compromised their roles in co-producing resilience in CBOW in northern Uganda. Participants identified having supportive connections with family—with mothers being the most accessible, and other people in the community, acquiring skills to engage in economic activities, supportive school environment, having a positive mind, and spirituality as important resilience-enhancing factors for CBOW.

This however did not mean that commonly known experiences of CBOW such as stigma and rejection had altogether disappeared. On the contrary, interviewees suggested that they still suffered stigma, rejection, health problems, poverty, and lack of economic opportunities, among others.

Limitations of the study

The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some conceptual, contextual and methodological limitations. First, whereas other studies have demonstrated that the CYRM-R has good psychometric properties, the current study did not evaluate reliability and consistency extensively due to limitations of time, and the study objectives. The study however noted the assumptions inherent in some of the items. Specifically, the statements “Friends stand by me when times are hard,” and “I feel that I belong at my school” assume that all of the targeted young people will have friends, and will be in school respectively. The current study applied all the 17 CYRM-R measures even when such statements did not apply. To ensure a robust outcome, the author used a mixed methods approach, which enabled a set of qualitative interviews with some of the respondents to complement and enrich the discussions of the findings regarding the CYRM-R. Thus, triangulation of data from the CYRM-R scores and the interviews supported and strengthened observations and discussions. Future investigations on validity and consistency of the measure for CBOW in different contexts and with larger samples can contribute in enriching the field.

Second, the CYRM-R is a standardized culturally sensitive measure. However, it does not have a Luo-version, for the language group (Lango) that participated in the study. The author translated the tool herself. In the absence of piloting the translated version, and to ensure some level of accuracy, the author had it back translated by an independent local Luo (Lango) speaker.

Third, whereas the study had set out to involve an equal number of male and female, female participants proved more difficult to recruit than male. Local contacts attributed this to stigma and early marriage. Families were prone to concealing their female CBOW's identity to increase future marriage prospects. Accordingly, the sample showed a skewed representation of the sexes, with males taking the larger share (n = 25) compared to females (n = 10).

Because the generalizability of convenience samples is unclear, the conclusions derived from the study sample may be biased, i.e., sample estimates may not be reflective of true effects among the larger CBOW population, as the sample may not accurately reflect the CBOW more generally.

Additional explorations to compare resilience in CBOW and non-CBOW, and the relationship between intergenerational harms and resilience (mothers of CBOW, CBOW and the children of CBOW), and how gender may influence resilience in CBOW in different contexts are recommended.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by LHIREC—Lacor Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Gulu, Uganda), accredited by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The field research was self-funded with additional primary data drawn from a (CSRS) study supported by the European Research Council under grant number 724518.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^See also: Ongwen Case. https://www.icc-cpi.int/uganda/ongwen.

2. ^Cattle raiding by rustlers from Karamoja led to the loss of millions of herds of cattle, with the human costs including killings, abduction, rape and forced marriages of children and women from Acholi, and Lango into Karamoja. Abductees have often found their way back into their old communities even after years of being held hostage, and many return with pregnancies or children of their own.

3. ^Dheeraj Akolkar (Vardo films). “The Wound is Where The Light Enters.” Available from: https://www.chibow.org/single-post/the-wound-is-where-the-light-enters-wins-at-the-ahrc-research-in-film-awards-2021 (accessed on 28 March, 2022).

4. ^Fieldwork notes for the CSRS study in northern Uganda, September 2019 to August 2020.

5. ^Participant UG-EOA-44 (CSRS study), Kilak county, Pader district in northern Uganda, 19 February 2019.

6. ^Already resilience scholar Theron et al. (2021) who has studied resilience in adolescents in southern Africa argue that Resilience is co-facilitated by individuals and their wider material and social-cultural environment, and that neither can do it alone.

7. ^The cattle rustling activities in northern Uganda is associated with groups from the Karamoja region.

References

Aburn, G., Gott, M., and Hoare, K. (2016).What is resilience? An integrative review of the empirical literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 72, 980–1000. doi: 10.1111/jan.12888

Akello, G. (2013). Experiences of forced mothers in Northern Uganda: the legacy of war. Intervention 11, 149–156. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e3283625d3c

Akello, G., Richters, A., and Reis, R. (2006). Reintegration of former child soldiers in northern Uganda: coming to terms with children's agency and accountability. Intervention 4, 229–243. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e3280121c00

Akhavan, P. (2005). The lord's resistance army case: Uganda's submission of the first state referral to the international criminal court. Am. J. Int. Law 99, 403–421. doi: 10.2307/1562505

Akullo, E. (2019). An Exploration of the Post-Conflict Integration of Children Born in Captivity Living in the Lord's Resistance Army War-Affected Areas of Uganda. (PhD Thesis), Department of Politics and International Relations, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Southampton, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom. Available online at: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/438627/1/Eunice_Akullo_Final_Thesis.pdf (accessed June 11, 2022).

Alessi, L., Benczur, P., and Campolongo, F. (2020). The resilience of EU member states to the financial and economic crisis. Soc. Indic. Res. 148, 569–598. doi: 10.1007/s11205-019-02200-1

Alessia, R., Eugenio, D., and Erin, B. (2021). ‘Our place under the sun': survivor-centred approaches to children born of wartime sexual violence. Hum. Rights Rev. 22, 327–347. doi: 10.1007/s12142-021-00631-3

Allen, T., Atingo, J., Atim, D., Ocitti, J., Brown, C., Torre, C., et al. (2020). What happened to children who returned from the lord's resistance army in Uganda? J. Refugee Stud. 33, fez116. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fez116

Allen, T., Atingo, J., and Parker, M. (2021). Rejection and resilience: returning from the lord's resistance army in northern Uganda. Civil Wars 2022, 2015195. doi: 10.1080/13698249.2022.2015195

Apio, E. (2016). Children Born of War in Northern Uganda: Kinship, Marriage, and the Politics of Post-Conflict Reintegration in Lango Society. (Dissertation), University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Arieff, A. (2010). Sexual Violence in African Conflicts. Congressional Research Service. Available online at: https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R40956.pdf (accessed March 16, 2022).

Baines, E. (2014). Forced marriage as a political project: sexual rules and relations in the lord's resistance army. J. Peace Res. 51, 405–417. doi: 10.1177/0022343313519666

Baum, N. L., Cardozo, B. L., Pat-Horenczyk, R., Ziv, Y., Blanton, C., Reza, A., et al. (2013). Training teachers to build resilience in children in the aftermath of war: a cluster randomized trial. Child Youth Care For. 42, 339–350. doi: 10.1007/s10566-013-9202-5

Betancourt, T. S., and Khan, K. T. (2008). The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 20, 317–328. doi: 10.1080/09540260802090363

Bimeny, P. P., Angolere, B. P. P., Saum, B., Nangiro, S., Sagal, A. I., and Joyce, E. J. (2021). From warriors to mere chicken men, and other troubles: an ordinary language survey of notions of resilience in ngakarimojong. Civil Wars 2022, 2015215. doi: 10.1080/13698249.2022.2015215

Bostock, L., Sheikh, A. I., and Barton, S. (2009). Posttraumatic growth and optimism in health-related trauma: a systematic review. J. Clin. Psychol. Medical Settings 16, 281–296. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9175-6

Bottrell, D. (2009). Understanding “marginal” perspectives: towards a social theory of resilience. Qualit. Soc. Work 8, 321–340. doi: 10.1177/1473325009337840

Buss, D., Lebert, J., Rutherford, B., Sharkey, D., and Aginam, O. (2014). Sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict societies. Int. Agendas African Contexts. Routledge African Stud. 2014, 9781315772950. doi: 10.4324/9781315772950

Calhoun, L. G., and Tedeschi, R. G. (2001). “Posttraumatic growth: the positive lessons of loss,” in Meaning Reconstruction and the Experience of Loss, ed R. A. Neimeyer (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 157–172. doi: 10.1037/10397-008

Carlson, K., and Mazurana, D. (2008). Forced Marriage Within the Lord's Resistance Army, Uganda. Feinstein International Centre. Available online at: http://fic.tufts.edu/assets/Forced+Marriage+within+the+LRA-2008.pdf (accessed February 28, 2022).

Carpenter, C. (2010). Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond. New York, NY; Chichester; West Sussex: Columbia University Press. doi: 10.7312/carp15130

Carpenter, R. C. (2007). Gender, Ethnicity, and Children's Human rights: Theorizing Babies Born of Wartime Rape and Sexual Exploitation in Born of War: Protecting Children of Sexual Violence Survivors in Conflict Zones, 1–;20. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

Cheong, S. P. S., Huang, J., Bendena, G. W., Tobe, S. S., and Hui, L. H. J. (2015). Evolution of ecdysis and metamorphosis in arthropods: The rise of regulation of juvenile hormone. Integrat. Compar. Biol. 55, 878–890. doi: 10.1093/icb/icv066

Christophe, L., Arnal, C., Wollast, R., Rolin, H., Kotsou, I., and Fossion, P. (2020). Perspectives on resilience: personality trait or skill? Eur. J. Trauma Dissoc. 4, 100074. doi: 10.1016/j.ejtd.2018.07.002

Clark, J. N. (2021). Vulnerability, space and conflict-related sexual violence: building spatial resilience. Sociology 55, 71–89. doi: 10.1177/0038038520918560

Cortes, L., and Buchanan, M. J. (2007). The experience of Colombian child soldiers from a resilience perspective. Int. J. Adv. Counsel. 29, 43–55. doi: 10.1007/s10447-006-9027-0

Dawadi, S., Shrestha, S., and Giri, R. A. (2021). Mixed-methods research: a discussion on its types, challenges, and criticisms. J. Pract. Stud. Educ. 2, 25–36. doi: 10.46809/jpse.v2i2.20

Denov, M., and Lakor, A. A. (2017). When war is better than peace: the post-conflict realities of children born of wartime rape in northern Uganda. Child Abuse Neglect 65, 255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.014

Dixon, A. (2018). Understanding Ecologies: PostConflict Service Provision and the Resilience of Children Born in Captivity. Available online at: https://sfxhosted.exlibrisgroup.com/dal?rft.atitle=Understanding%20Ecologies%3A%20PostConflict%20Service%20Provision%20and%20the%20Resilience%20of%20Children%20Born%20in%20Captivity&rft.aulast=Dixon&rft.aufirst=Alina (accessed March 16, 2022).

Esuruku, R. S. (2011). Beyond masculinity: gender, conflict and post-conflict reconstruction in northern Uganda. J. Sci. Sustain. Dev. 4, 25–40. doi: 10.4314/jssd.v4i1.3

Ferrari, M., and Fernando, C. (2013). “Resilience in children of war,” in Handbook of Resilience in Children of War, eds C. Fernando and M. Ferrari (New York, NY: Springer), 7. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6375-7

Garbarino, J. (1995). Raising Children in a Socially Toxic Environment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Green, L., Fisher, E. B., Perlow, S., and Sherman, L. (1981). Preference reversal and self-control: choice as a function of reward amount and delay. Behav. Anal. Lett. 1, 43–51.

Gretchen, B., Rossman, A., and Wilson, B. L. (1985). NUMBERS and WORDS: combining wualitative and quantitative methods in a single large –scale evaluation study. Eval. Rev. 9, 627–643. doi: 10.1177/0193841X8500900505

Han, S. S., and Kim, K. M. (2006). Influencing factors on self-esteem in adolescents. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi 36, 37–44. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2006.36.1.37

Henshall, C., Davey, Z., and Jackson, D. (2020). Nursing resilience interventions – a way forward in challenging healthcare territories. J. Clin. Nurs. 29, 3597–3599. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15276

Hoegl, M., and Hartmann, S. (2021). Bouncing back, if not beyond: challenges for research on resilience. Asian Bus Manage 20, 456–464. doi: 10.1057/s41291-020-00133-z

HRW (2010). “As if We Weren't Human”: Discrimination and Violence against Women with Disabilities in Northern Uganda. Available online at: hrw.org/report/2010/08/26 (accessed March 16, 2022).

ICPALD (2019). ‘Uganda Cattle Rustling', IGAD centre for Pastoral Areas and Livestock Development. Available online at: https://icpald.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/UGANDA-CATTLE-RUSTLING-FINAL.pdf (accessed April 18, 2022).

Janine Clark, N. (2021). Beyond a ‘survivor-centred approach' to conflict-related sexual violence? Int. Affairs 97, 1067–1084. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiab055

Jeffery, R. (2011). Forgiveness, amnesty and justice: the case of the Lord's Resistance Army in northern Uganda. Cooperat. Conflict 46, 78–95. doi: 10.1177/0010836710396853

Kirschenbaum, A. L. (2017). The meaning of resilience: soviet children in world war II. J. Interdiscipl. Hist. 47, 521–535. doi: 10.1162/JINH_a_01053

Klasen, F., Oettingen, G., Daniels, J., Post, M., Hoyer, C., and Adam, H. (2010). Posttraumatic resilience in former Ugandan child soldiers: posttraumatic resilience. Child Dev. 81, 1096–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01456.x

Ladisch, V. (2015). What Future for Children Born of War? ICTJ. Available online at: https://www.ictj.org/news/uganda-children-war-social-stigmatization (accessed February 11, 2022).

Lee, S., Glaesmer, H., and Stelzl-Marx, B. (2021). Children Born of War: Past, Present and Future. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429199851

Liebenberg, L., Ungar, M., and Vijver, F. V. de. (2012). Validation of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure-28 (CYRM-28) among Canadian youth. Res. Soc. Work Practice 22, 219–226. doi: 10.1177/1049731511428619

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., and Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 71, 543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164

Masten, A. S., Hubbard, J. J., Gest, S. D., Tellegen, A., Garmezy, N., and Ramirez, M. (1999). Competence in the context of adversity: pathways to resilience and maladaptation from childhood to late adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 11, 143–169. doi: 10.1017/S0954579499001996

McAdam-Crisp, J. L. (2006). Factors that can enhance and limit resilience for children of war. Childhood 13, 459–477. doi: 10.1177/0907568206068558

Meaghan, C. S., and Denov, M. S. (2021). A multidimensional model of resilience: family, community, national, global and intergenerational resilience. Child Abuse Neglect 119, 105035. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105035

Mochmann, I. C., and Larsen, S. U. (2008). The forgotten consequences of war: the life course of children fathered by German soldiers in Norway and Denmark during WWII – some empirical results. Historical Soc. Res. 33, 347–363.

Mukasa, N. (2017). War-child mothers in northern Uganda: the civil war forgotten legacy. Dev. Practice 27, 354–367. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2017.1294147

Neenan, J. (2017). Closing the Protection Gap for Children Born of War – Addressing Stigmatisation and the Intergenerational Impact of Sexual Violence in Conflict. LSE & FCO. Available online at: http://www.lse.ac.uk/women-peace-security/asets/documents/2018/LSE-WPS-Children-Born-ofWar.pdf (accessed April 11, 2022).

Ojiambo, R. (2005). “The efforts of non-governmental organizations in assessing and documenting the violations of women's human rights in situations of armed conflict: the Isis- WICCE experience,” in Expert paper prepared by Isis-WICCE for the UNDAW Expert Group Meeting, Geneva. Available online at: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/vaw-stat2005/docs/expertpapers/Ochieng.pdf (accessed March 04, 2022).

Opio, M. L. (2015). Alone Like a Tree: Reintegration Challenges Facing Children Born of War and Their Mothers in Northern Uganda. Justice and Reconciliation Project. Available online at: http://justiceandreconciliation.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Alone-Like-A-Tree-Reintegration-Challenges-Facing-Children-Born-of-War-and-Their-Mothers-in-Northern-Uganda1.pdf (accessed March 11, 2022).

Peltonen, K., Qouta, S., Diab, M., and Punamäki, R.-L. (2014). Resilience among children in war: the role of multilevel social factors. Traumatology 20, 232–240. doi: 10.1037/h0099830

Pham, P., Vinck, P., and Stover, E. (2007). Abducted: The Lord's Resistance Army and Forced Conscription in Northern Uganda. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1448370

Pham, P. N., Vinck, P., and Stover, E. (2009). Returning Home: forced conscription, reintegration, and mental health status of former abductees of the Lord's Resistance Army in Northern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry 9, 23. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-23

Ramos, C., Leal, I., and Tedeschi, R. G. (2016). Protocol for the psychotherapeutic group intervention for facilitating posttraumatic growth in nonmetastatic breast cancer patients. BMC Women's Health. 16, 22. doi: 10.1186/s12905-016-0302-x

Refugee Law Project. (2014). Compendium of All Conflicts in Uganda 2014 – Refugee Law Project, Makerere School of Law. Available online at: https://www.scribd.com/document/329312966/Compendium-of-all-conflicts-in-Uganda-2014-Refugee-Law-Project-makerere-school-of-Law (accessed March 10, 2022).

Resilience Research Centre (2018). CYRM and ARM User Manual. Halifax, NS: Resilience Research Centre, Dalhousie University. Available online at: http://www.resilienceresearch.org/ (accessed March 10, 2022).

Roper, L. (2019). An Ecological Approach to Resilience is Essential. Available online at: https://thepsychologist.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/articles/pdfs/0519bennett.pdf?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA3JJOMCSRX35UA6UU%2F20220209%2Feu-west-2%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20220209T094512Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=Host&X-Amz-Expires=10&X-Amz-Signature=2d60aa93f73c85ebd304e47b16bdbf7fe63ff4f76409358c11798fdc8719c91b (accessed March 28, 2022).